Despite clear statements and acknowledgments by federal officials and several committee members at last week’s Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) meeting that nirsevimab is not a vaccine, this U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drug will essentially be treated as a vaccine by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

This action is due to the CDC committee’s determination that “vaccine” is not well defined in federal statute. Therefore, the new drug manufactured by Sanofi and Astra Zeneca is eligible for inclusion in the federally recommended childhood vaccination schedule and in the federally funded Vaccines for Children Program (VFC).

The ACIP vote to treat the new genetically engineered RSV drug as a vaccine for the purpose of adding it to the recommended childhood vaccination schedule, opens the door to adding the fake vaccine to state mandates for daycare attendance and giving Sanofi and Astra Zeneca a liability shield from vaccine injury lawsuits by adding it to the federal Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP).

.png)

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) is a common infection in infants and young children with symptoms similar to the cold that circulates primarily from the fall to end of spring.1 Most children will have experienced an RSV infection by age two and recovered without serious complications.2 3 Infants and children at high risk for complications, such as inflammation of the lungs and pneumonia, include full-term infants, premature infants, children with congenital health and lung disorders or those who are immunocompromised.4 It is estimated that one to two RSV cases out of 100 will require hospitalization.5

The committee voted unanimously that all healthy infants under eight months old receive one injection of nirsevimab, and that children between eight months and 19 months of age at high risk for severe RSV receive an injection of the drug in their second RSV season.6 Additionally, the committee voted unanimously for this fake vaccine to be added to the VFC funding program, which provides childhood vaccines to underserved and uninsured children at no cost to remove financial barriers to vaccination.7 You can read NVIC’s written public comment submitted to the ACIP, noting the clear documentation that nirsevimab is not a vaccine and our request for the VFC vote to be tabled.

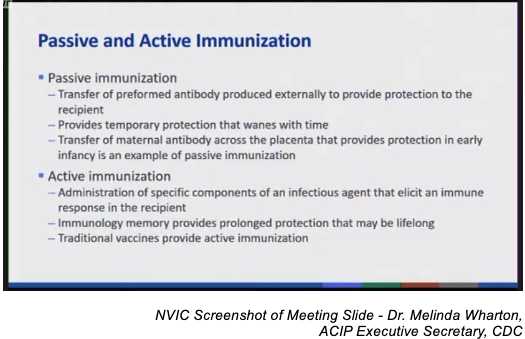

The CDC presented the committee with definitions for “passive immunity” and “active immunity”, the latter of which was noted as being provided by vaccines.

Nirsevimab Approved by FDA as a Drug

Nirsevimab is a genetically engineered monoclonal antibody designed to passively provide immunity to RSV and was approved by the FDA for licensure as a drug under the trade name Beyfortus on July 17, 2023.8 9 The basis for licensure was in part the recommendation from the FDA’s Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee (AMDAC), which evaluates data on drug products for use in treating infectious diseases and disorders,10 11 12 rather than the FDA’s Vaccines & Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC), which evaluates scientific evidence for the safety and efficacy of new vaccines, which and has made no such recommendation.13 14 15

During the meeting, ACIP committee members criticized the American Medical Association (AMA) for its CPT billing code designation of nirsevimab,16 even though the World Health Organization and FDA do not classify nirsevimab as a vaccine.17 18

Nirsevimab Vote Triggers Potential State Mandates and Challenges for Vaccine Registries

The ACIP’s votes will undoubtedly have a ripple effect at the state and federal levels. There is the potential for state daycare mandates and tracking in state vaccine registries, while at a federal level there is the potential for nirsevimab to be added to the federal VICP.

Implementation challenges identified in treating nirsevimab as a vaccine include data-sharing between electronic medical records (EMR) with state vaccine tracking registries and state laws that may prohibit some vaccinators from administering the drug to infants and children. However, the number of states with such scope of practice issues was thought to be small, and work has already begun to address coding issues related to data-sharing between EMRs and vaccine registries.

Politics of Costly RSV Drug

The addition of nirsevimab to the VFC program is likely partly due to its private sector price tag of $495/dose. However, the VFC designation only reduces that cost to $395/dose and was criticized by committee members as too costly.

The VFC’s funding comes through an entitlement program under Section 1928 of the Social Security Act.19 Vaccines administered through the VFC program are at no cost to the child, but are not “free” because VFC funding comes from federal tax dollars and by law each state is required to participate through Medicaid.20 21 22

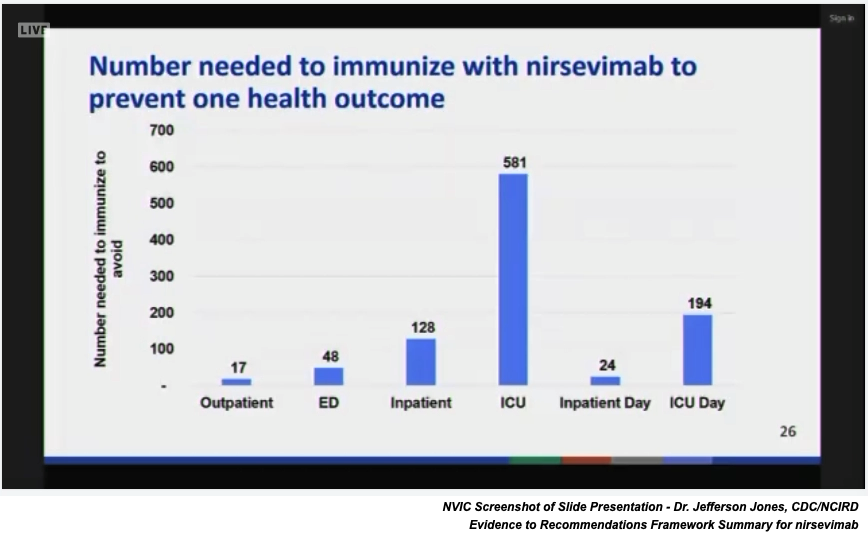

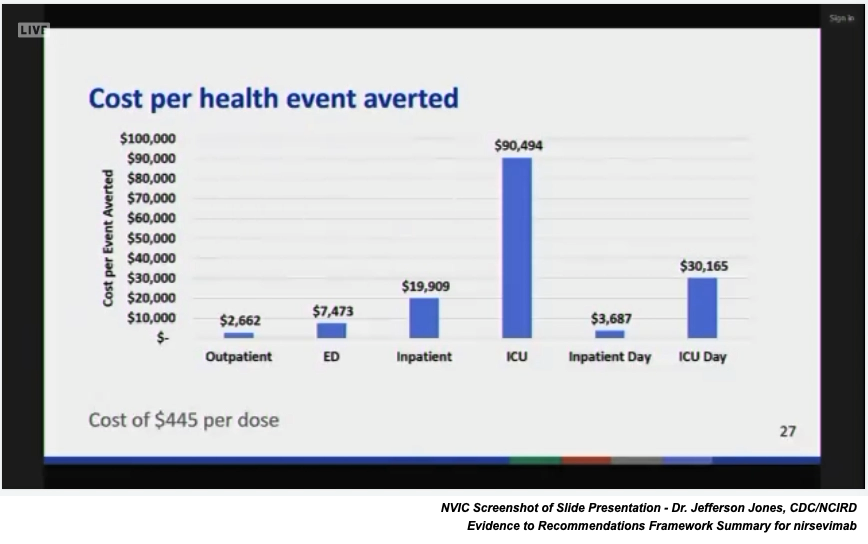

Updated resource use costs for the fake vaccine nirsevimab were reported to the committee. The CDC’s updated data included the following assumptions: 1) average price of $445/dose based on 50% VFC and 50% private insurance funding; 2) inclusion of individuals at increased risk of severe RSV; 3) savings from not using palivizumab (an existing RSV monoclonal antibody).

Notably, the latest birth report for the U.S. states that in 2021 3.66 million births occurred in the U.S.23 If birth rates in the U.S. remain about the same, the nirsevimab universal use recommendation by the ACIP, based on the $445 per dose cost and 100 percent uptake, represents an annual cost of about $1.6 billion. Sanofi and Astra Zeneca are marketing the new fake vaccine.

Nirsevimab Adverse Event Reporting and Federal Injury Compensation

CDC’s officials also stated that educational risk/benefit materials are under development for nirsevimab and will look similar to vaccine information statements (VIS) that are federally required under the 1986 National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act to be provided to parents and guardians before vaccinating a minor child. Additional materials are being developed to assist vaccinators in handling questions about why nirsevimab is being recommended like a vaccine, given that it is not a vaccine.

Committee members also asked about (1) the safety of co-administering a vaccine with the monoclonal antibody drug; (2) whether nirsevimab would be included in the VICP and (3) what mechanism would be used to report nirsevimab adverse events.

Concerning co-administration of nirsevimab with other vaccines, public health officials presenting data during the meeting stated that it was thought to be safe to co-administer nirsevimab with other vaccines because nirsevimab is not a vaccine.

Monitoring of adverse events has been split between two systems. Adverse events occurring after a child receives nirsevimab along with a vaccine will be reported to the federal Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). However, when nirsevimab is administered with no vaccines, adverse events will be reported to the FDA's Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) used for drugs and therapeutic biological products.

Questions relating to nirsevimab injury claims were deferred to Commander Reed Grimes, M.D. of the federal Division of Injury Compensation Programs within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Grimes provided an overview of the 1986 law governing the VICP and the steps required for inclusion in the program:

- CDC must recommend a vaccine for routine use in children or pregnant women;

- Congress must enact an excise tax on the vaccine; and

- the U.S. Secretary for the Department of Health and Services must add it to the VICP’s Vaccine Injury Table (VIT).24

He added that if these steps were taken for nirsevimab, due to the lack of specific definition for vaccine within the 1986 Act, he believed that nirsevimab could be added to the VICP.

The first step – adding the monoclonal antibody to the vaccine schedule – has been accomplished. Now the door is open for Sanofi and Astra Zeneca, the manufacturers of the fake vaccine, to be handed a liability shield by adding the product to the VICP.

What You Can Do

The anticipated schedule for rolling out the fake RSV vaccine is this Fall and co-administering it with the birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine. If you do not want your infant to receive nirsevimab, read NVIC’s FAQ on infant hepatitis B vaccine at birth and details about standing orders and standard of care policies in hospitals, which may include not requiring parents to give written informed consent before newborns are injected with the monoclonal antibody drug and hepatitis B vaccine.

Visit NVIC’s RSV webpages to learn about RSV and nirsevimab so you can make an informed decision. NVIC.org also has information about daycare laws in your state. If your daycare has added nirsevimab as a requirement for attendance, ask for a copy of the statute or administrative rule that requires it. Consider getting legal advice about your options and verification of the requirement.

Register for free online NVIC’s Advocacy Portal to easily connect with your legislators and communicate your concerns about treating this drug like a vaccine and the potential for mandates. Visit the Portal often to stay current on legislation to mandate nirsevimab.

References:

1 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms and Care. In: Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (RSV). Oct. 24, 2022.

2 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms and Care. In: Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (RSV). Oct. 24, 2022.

3 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms and Care. In: Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (RSV). Oct. 24, 2022.

4 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in Infants and Young Children. In: Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (RSV). Oct. 28, 2022.

5 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in Infants and Young Children. In: RSV References & Resources. Oct. 27, 2022.

6 U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Recommends a Powerful New Tool to Protect Infants from the Leading Cause of Hospitalization. Aug. 3, 2023.

7 U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for Children Program (VFC). Oct. 24, 2022.

8 U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA NEWS RELEASE - FDA Approves New Drug to Prevent RSV in Babies and Toddlers. July 17, 2023.

9 U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Beyfortus Biologic License Application (BLA): 761328. In: Drug Databases – Drugs@FDA: FDA – Approved Drugs. Accessed Aug. 4, 2023.

10 AstraZeneca. Nirsevimab BLA 761328 - Briefing Document for June 8, 2023 Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting. U.S. Food & Drug Administration May 17. 2023.

11 U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee (formerly known as the Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee). Accessed: Aug. 2, 2023.

12 U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Charge to the Committee - Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee. June 8, 2023.

13 U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 2023 Meeting Materials, Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee. Accessed: Aug. 2, 2023.

14 U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 182 nd Meeting of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) Transcript. June 15, 2023.

15 U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research SUMMARY MINUTES 181st VACCINES AND RELATED BIOLOGICAL PRODUCTS ADVISORY COMMITTEE. May 18, 2023.

16 American Medical Association. CPT Category | New Immunization* Vaccine Codes (Including Incorporation of ACIP Abbreviations Listing) Long Descriptors. Aug. 2, 2023.

17 WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. J06BD Antiviral monoclonal antibodies. Jan. 23, 2023.

18 WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. J07B VIRAL VACCINES. Jan. 23, 2023.

19 Social Security. PROGRAM FOR DISTRIBUTION OF PEDIATRIC VACCINES. In: Compilation of the Social Security Laws. Accessed: Aug. 2, 2023.

20 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Vaccine Price List. Aug. 3, 2023.

21 Cole M. The Vaccines for Children Program (VFC). National Center for Health Research Accessed: Aug. 9, 2023.

22 Cussen MP. How Much Medicaid and Medicare Cost Americans. Investopedia Mar. 11, 2022.

23 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Births and Natality. In National Center for Health Statistics. June 8, 2023.

24 U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration. Email Correspondence - EUA Vaccines and VICP. National Vaccine Information Center Aug. 24-30, 2021.

.png?width=991&height=280&ext=.png)

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with an *