Read and report vaccine reactions, harassment and failures.

Measles: The Disease

Measles (rubeola) is a highly contagious respiratory disease spread by coughing, sneezing, or simply being in close contact with an infected individual. The disease can be spread even when the rash is not visible. Measles tends to be more severe in children under five and adults over 20. Initial measles symptoms include fever, cough, runny nose, red irritated eyes, and sore throat with tiny white spots on the cheeks inside the mouth (Koplik spots). These symptoms generally last 2-4 days and are followed by the signature itchy red rash on the body around the fourth or fifth day.

Most measles cases in the U.S. resolve without complication, though serious complications can occur. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Americans born before 1957 have naturally-acquired immunity to measles through past exposure to the illness. Infants born to mothers with naturally-acquired antibodies to measles benefit from passive maternal immunity. There is also evidence that mothers who have recovered from measles pass short-term measles immunity to their infants by breastfeeding. Learn more about Measles…

Measles Vaccine

The measles vaccine is a weakened (attenuated) form of the live measles virus. There are three live virus vaccines currently available for use in the U.S.: Merck's MMRII vaccine containing measles, mumps, and rubella attenuated live viruses; Merck's Proquad (MMRV) vaccine containing measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella attenuated live viruses; and GlaxoSmithKline’s PRIORIX containing measles, mumps, and rubella attenuated live viruses. The CDC currently recommends that children receive two doses of a measles containing vaccine, with the first dose administered between 12-15 months and the second dose between 4-6 years. The CDC also recommends that individuals born after 1957 who have no laboratory evidence of immunity or documentation of vaccination should receive at least one dose of MMR vaccine. Learn more about Measles vaccine…

Measles Quick Facts

Measles

- After coming in contact with someone infected with measles, the incubation period to onset of the rash is between 7 and 21 days, with an average of 14 days. The period leading up to the appearance of the rash is characterized by a rising fever that peaks at 103-105 degrees F.

- Three years beforethe first measles vaccine became available in 1960, there were approximately 442,000 reported measles cases and 380 related deaths in the U.S. among the 3.5 to 5 million Americans likely infected with measles. Measles-associated deaths are rare in the U.S., with the last reported death occurring in 2015. Continue reading quick facts…

Measles Vaccine

- There are three measles vaccines currently in use in the United States. Two vaccines, MMRII and PRIORIX, are combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) live virus vaccines. The third, ProQuad, is a combination measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMR-V) live virus vaccine. Both MMRII and ProQuad are manufactured and distributed by Merck, while PRIORIX is manufactured and distributed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). The CDC recommends children receive the first dose of MMR vaccine between 12 and 15 months and the second dose between 4 and 6 years.

- As of March 29, 2024, there have been 112,733 reports of measles-vaccine reactions, hospitalizations, injuries, and deaths following measles vaccinations made to the federal Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS), including 560 related deaths, 8,639 hospitalizations, and 2,162 related disabilities. Over 50 percent of those adverse events occurred in children three years old and under. Continue reading quick facts...

NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents below, which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

What is Measles (Rubeola)?

Measles (Rubeola) is a respiratory disease caused by a paramyxovirus, genus Morbillivirus with a core of single-stranded RNA. Measles is highly contagious and causes a systemic infection that begins in the nasopharynx (upper area of the throat behind the nose). The virus is highly contagious but it can easily be destroyed by light, high temperatures, UV radiation or disinfectants. Measles viruses are divided into eight clades (A to H) and while 24 genotypes have been confirmed, only 19 have been detected since 1990.

Measles causes a systemic infection that begins in the nasopharynx. The virus is transmitted through respiratory secretions (nasal discharge, coughing sneezing) and an infected person is contagious for four days prior to the onset of symptoms up until four days after rash onset.

Measles is unique to humans. Before the first measles vaccine was licensed for use in the U.S. in 1963, measles cases and outbreaks were seen generally in late winter and spring usually every two to three years.

Measles symptoms begin 10-14 days after close contact with someone infected with measles. Symptoms start with a fever, cough, runny nose, conjunctivitis, and white spots in the mouth, and progresses to a rash that starts on the face, spreads to the rest of the body, and lasts for about a week. Prior to the appearance of the measles rash (on the fourth or fifth day after fever begins), measles can be mistaken for several illness including influenza, bronchiolitis, croup, or pneumonia.

Other symptoms of measles include:

- Light sensitivity

- Watery eyes

- Sneezing

- Body aches

- Swollen eyelids

Illnesses that may also develop along with measles are ear infections, diarrhea, croup, bronchiolitis and pneumonia.

Measles complications include very high fever, diarrhea, otitis media, seizures, pneumonia, encephalitis and are recported to occur at one tenth of one percent of cases. Very rarely, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE - a progressive, debilitating and deadly brain disorder), and death also occur. Measles during pregnancy may result in a premature birth or a low birth-weight infant. Recovery from measles will create antibodies that confer long-lasting immunity.

In the past, when measles infections were common, doctors diagnosed measles from the presence of tiny white specks surrounded by a red halo inside the cheeks of an infected person’s mouth. However, as measles is no longer common, the measles rash has been frequently misdiagnosed by physicians as scarlet fever, Kawasaki Disease, and dengue. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) urges healthcare providers to consider measles when a patient presents with a febrile rash, and to notify the local health department of any suspected cases within 24 hours.

Confirmation of measles must be made by laboratory diagnosis (blood, throat swab) as physician reports of measles cases based on symptoms are no longer accepted by the CDC as confirmation of the disease. Additionally, measles genotyping should be completed as this is the only way to determine whether a person has wild-type measles or a rash as a result of a recent measles vaccination (vaccine-strain measles).

“Modified” measles can also occur in persons with some degree of immunity, as well as in previously vaccinated persons, who get a milder form of measles. “Atypical” measles can occur in a person who was previously vaccinated with a killed-virus vaccine used from 1963 to 1967 and who is exposed to wild-type measles. The course of atypical measles is generally longer than natural measles.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Is Measles contagious?

Measles is a highly-contagious viral disease that is spread through the air by respiratory droplets (coughing, sneezing, etc) or by coming in contact with nasal discharge/mucous of an infected person.

Measles is most contagious during the three days before the rash appears. The rash usually begins as red flat spots on the face and neck and works its way down the body towards the feet. Raised red bumps may also appear on the flat red spots and as the rash spreads downwards, the spots may join together. Fever may also occur when the rash first appears. The rash lasts 3-7 days and fades in the order in which it appeared. The fever can linger 2-3 more days, and the cough can last for up to 10 days after the rash has subsided.

Measles can be easily transmitted inclose quarters; for example, by family members at home, students in schools or children in daycare centers, or between travelers using public transportation. Other settings for transmission of measles may include public places where large numbers of people gather and have close contact. Measles transmission in a susceptible person has been documented up to 2 hours after a contagious person has left the room.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Americans born before 1957 have naturally-acquired immunity to measles through past exposure to the illness. Infants born to mothers with naturally-acquired antibodies to measles benefit from passive maternal immunity. There is also evidence that mothers who have recovered from measles pass short-term measles immunity to their infants by breastfeeding.

Conversely, recent medical literature reports that infants born to vaccinated mothers have lower levels of maternal antibodies and lose them earlier compared to infants whose mothers had developed natural immunity from prior measles infection. As a result, most infants born to vaccinated mothers are at a high risk of developing measles due to the poor quality and shorter duration of maternal antibodies.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

What is the history of measles in America and other countries?

Measles was first described in the 9th century by Persian physician-philosopher Zakariya Razi. His accurate description of measles was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1970 as the first written account of the illness.

In 1757, Scottish physician Francis Home concluded that measles was an infection of the respiratory tract and could be found in the blood of affected individuals. Home attempted to develop a measles vaccine, however, his vaccine experiments were not successful as the measles virus had not yet been isolated. In 1954, Dr. Thomas C Peebles and Dr. John F. Enders successfully isolated the measles virus during an outbreak among students in Boston, Massachusetts. Measles vaccination development began shortly after their discovery.

In the U.S., measles became a reportable disease in 1912. In 1920, there were 469,924 recorded cases and 7,575 deaths associated with measles. Increases in measles cases generally occurred in late winter and spring, every two to three years.

Prior to measles vaccine licensing in 1963, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) admitted that measles cases were significantly underreported “because virtually all children acquired measles, the number of measles cases probably approached 3.5 million per year (.i.e., an entire birth cohort).” Other experts reported that up to 5 million measles occurred yearly in the United States.

In 1960, three years before the first measles vaccine was approved for use in the U.S., there were approximately 442,000 reported measles cases and 380 related deaths among the 3.5 to 5 million Americans who likely were infected with measles. In 1969, measles deaths were estimated at 1 in 10,000 cases.

The CDC attributes the drop in reported measles cases and deaths in the U.S. to use of the measles vaccine beginning in the mid-1960’s; However, published measles morbidity and mortality data give evidence that death rates for measles had dropped significantly in the U.S. before the measles vaccine was introduced in 1963.

In 1967, public health officials announced that measles could be eradicated from the U.S. within a few months, with the introduction and use of measles vaccines. However, mass vaccination of children beginning at approximately one year of age and the push for all children entering school to receive a dose of measles vaccine did not result in eradication and outbreaks of measles continued to occur in highly vaccinated populations. By the end of 1968, 22,231 measles cases had been reported to the CDC.

In the 1970s, attempts were made to use MMR, Merck’s newly licensed live virus vaccine which combined the attenuated measles vaccine with live mumps and rubella vaccine, to eradicate measles by employing surveillance and containment strategies that worked to eradicate smallpox. This was attempted despite knowledge that the highly contagious measles vaccine was very different than the less contagious smallpox virus. The eradication campaign was a complete failure and measles cases and outbreaks continued.

In 1979, public health officials launched an effort to eliminate measles in the United States through vaccination, with a goal of elimination by October 1, 1982. In 1982, there were a record low 1,697 reported cases of measles in the United States and while public health officials conceded that the goal of elimination had not been met, they publicly stated that it was “right around the corner”.

From 1985 to 1988, there were between 55 and 110 measles outbreaks every year in the U.S., primarily in highly vaccinated school-aged populations. Measles swept through a middle school in Texas, where 99 percent of the students were vaccinated, and in a Massachusetts high school with a 98 percent vaccination rate.

A resurgence of measles in the United States occurred between 1989 and 1991, when reported measles cases increased 6- to 9-fold over the previously studied period between 1985 and 1988. This resurgence was associated with unusually high morbidity and mortality. While the CDC stated that they didn’t know why there were increases in measles and insisted that “measles vaccines appear to be as effective today as in the past,” they also admitted that the “analysis of contemporary strains of measles virus suggest that circulating viruses may have changed somewhat from past strains.”

There were more than 45,000 measles cases reported in the U.S. between 1989 and 1990, and over 100 deaths. Many cases occurred among vaccinated school children; however, a large number of cases also occurred in babies less than 15 months old, in unvaccinated toddlers, as well as in college students.

As a result of the significant increase in the number of reported measles cases, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) changed its measles recommendation, and all children were advised to receive an additional dose of measles vaccine prior to school entry.

Reported measles cases dropped by the early 1990’s and in an eight-year period between 1993 and 2001, there were 1804 cases and 120 outbreaks reported. In 2000, when only 86 measles cases were reported, the CDC declared measles to be eliminated in the United States.

From 2000 to 2007, the U.S. recorded an average of 63 cases of measles a year. Measles cases increased slightly in 2008 to 140 reported cases, but decreased again in both 2009 and 2010. In 2011, 220 cases were reported and frequently associated with travelers returning from European and Southeast Asian countries.

In 2014, there were 667 reported measles cases, and many cases were linked to the Philippines, which was experiencing a significant measles outbreak. 383 cases were associated with an outbreak involving an Amish community in Ohio.

In January 2015, a multi-state outbreak linked to a California amusement park resulted in 147 confirmed cases of measles. No known outbreak source was confirmed; however, the CDC believes that an international traveler was likely responsible for the outbreak. The particular measles strain responsible for the California outbreak was reported by the CDC to be identical to a strain found in the Philippines.

The 2015 measles outbreak prompted a media firestorm, with newspapers and health officials blaming the parents of unvaccinated children for outbreaks, calling them ignorant, anti-science, and worse. Many state legislators responded quickly by introducing vaccine legislation aimed at eliminating or severely restricting religious and conscientious/philosophical vaccine exemptions. Vaccine choice advocates were highly successful in defeating most bills, however, California lost its personal belief exemption and Vermont lost its philosophical exemption but retained its religious exemption.

In 2017, a published study revealed that in 2015, of the 194 measles virus specimens collected and analyzed, 73 were determined to be vaccine-strain. While referred to by the CDC as a vaccine reaction, a rash and fever occurring 10-14 days following vaccination is indistinguishable from wild type measles and requires confirmation by genotyping (specific testing that can determine whether the virus is wild-type or vaccine strain). Measles genotyping is important and multiple studies on vaccine-strain measles have reported on the need for rapid genotyping to quickly differentiate between wild and vaccine-strain measles, especially during an outbreak.

In 2017, a 75-case outbreak occurred in Minnesota and affected mainly Somalian Americans living in Minneapolis. A total of 122 cases of measles were reported in 2017.

349 measles cases and 17 separate outbreaks were reported to the CDC between January 1 and December 29, 2018 and cases were reported in 26 states and the District of Columbia.

In January 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced “vaccine hesitancy” to be one of the top ten global health threats. By late January, as a result of the rising number of reported measles cases in the U.S., the government and media launched an unprecedented response.

In Rockland County, New York instead of quarantining people infected with measles, government officials threatened parents of healthy unvaccinated children with fines and imprisonment if their children appeared in public spaces – the first time ever in American history. Unvaccinated children and adults living, working or visiting in neighborhoods with certain zip codes in Brooklyn were threatened with steep fines if found in contact with someone with measles.

Several state legislatures, including Arizona, New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, Minnesota, Iowa, Alabama, Missouri, Maine, Massachusetts, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Wisconsin, introduced bills to eliminate religious and conscientious/philosophical vaccine exemptions for school entry. In California, a bill was introduced and amended to severely restrict its medical exemption.

Washington State passed a bill which eliminated the philosophical exemption for MMR vaccine, and Maine’s legislature removed its religious and philosophical exemption for all vaccines. On June 13, 2019, the New York State legislature repealed its religious exemption to vaccination in one day, without permitting any public hearings.

From January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019, 1,282 cases of measles in 31 states were reported. Most reported cases and outbreaks were associated with travelers from countries such as the Ukraine, Israel, and the Philippines, where large outbreaks were occurring.

Measles is a common infection seen in many developing countries, especially in Asia and Africa. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 110,000 measles related deaths occurred globally in 2017 and most deaths involved children under the age of 5. Complications occur more frequently in young children who are malnourished and insufficient in vitamin A. Children with immunosuppressive diseases, such as HIV, are also more likely to suffer from complications.

Measles re-emerged globally in 2019 and by mid-April that year, WHO had reported 112,000 cases impacting 170 countries. WHO officials said that this likely reflected about 10 percent of all cases.

In 2020, only 13 measles cases were reported in the U.S. Cases in 2021 increased slightly, with 49 cases reported.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Can Measles cause injury and/or death?

Complications from measles are usually most frequent among children under 5 and adults over 20. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reports that approximately 30 percent of all reported measles cases result in at least one complication.

The most frequently reported complications are diarrhea, ear infection, and pneumonia. Additional measles complications can include bronchitis, croup, seizures, appendicitis, hepatitis, inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis), thrombocytopenia, encephalitis, and rarely death. Measles during pregnancy may result in miscarriage, premature, or low-birth-weight baby.

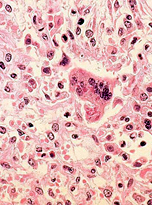

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a rare but fatal progressive central nervous system disorder, may also occur after a measles. SSPE is believed to be the result of a persistent measles infection of the brain. Signs of SSPE include personality changes, sleep disturbances, distractibility, gradual onset of mental deterioration, muscle spasms, and an elevated anti-measles antibody of the blood and cerebrospinal fluid. SSPE usually occurs an average of 7 years after a measles infection, (range – 1 month to 27 years). It is believed to occur in the U.S. in 5-10 cases per million reported measles infections.

In developing countries, measles is one of the leading causes of death in children. In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) attributed 110,000 deaths to measles infection, with most deaths occurring in children under age 5. In these countries, serious malnutrition, vitamin A deficiency and immunosuppressive diseases such as HIV/AIDS often lead to more severe cases of measles and a higher death rate.

Measles is rarely fatal in the United States, and historically, measles-related deaths have been reported in only 1 out of 10,000 cases. The last measles-related death in the United States was reported in 2015. In this case, that death occurred in an immunocompromised woman who was previously vaccinated for measles. Initially, her death was reported to be related to pneumonia; however, on autopsy, the measles virus was isolated, which prompted a revision to her cause of death.

While measles infection occasionally causes injury and/or death, recovery from measles may improve one’s health.

In published medical literature, recovery from measles has been shown to improve health outcomes of persons with kidney disease and nephrotic syndrome. Remission of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis have also been documented after recovery from measles. A positive history of measles infection prior to college was found to reduce the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Additionally, a case study published in the British Medical Journal reported remission of Hodgkin’s disease and the complete disappearance of a cervical tumor on recovery from measles. In 2015, Japanese researchers reported that a positive history of measles and mumps decreased a person’s risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Who is at highest risk for getting Measles?

Persons most at risk for developing measles are poorly nourished young children, especially those with insufficient vitamin A, or those whose immune systems have been weakened by HIV/AIDS or other diseases. Crowded living conditions can also put people at high risk of contracting measles, even in highly-vaccinated populations.

The vaccine acquired immunity that most mothers pass on to their infants has been found to be much lower and shorter acting than those produced following natural measles infection, placing these infants at higher risk for measles infection. Children vaccinated prior to the waning of maternal measles antibodies may also be at risk of measles. Published research has determined that vaccination in the presence of maternal antibodies can reduce the effectiveness of the measles vaccine, even after boosting with additional vaccine doses.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Who is at highest risk for suffering complications from Measles?

Children under 5 and adults over 20 are most at risk for complications from measles. Undernourished or vitamin A-deficient children, and individuals with immunosuppressive diseases such as HIV/AIDS, are at highest risk of severe complications. Persons with congenital immunodeficiencies and those requiring chemotherapeutic and immunosuppressive therapy are also at a high risk for complications from measles. Adults who contract measles are more at risk of developing acute measles encephalitis than children.

Pregnant women who contract measles may be at higher risk for developing complications including miscarriage, pre-term labor, and low birth weight infants. Birth defects have not been associated with measles infection.

Studies also show that complication rates and deaths are significantly higher, and recovery times longer, in infants and children who acquire measles in healthcare settings such as hospitals.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Can Measles be prevented and are there treatment options?

The treatment of measles primarily involves alleviating symptoms with fluids and fever-reducers. Rest is recommended and use of a humidifier may be helpful to soothe a sore throat or cough. Complications such as encephalitis and pneumonia may occur and careful monitoring of symptoms is recommended.

Many studies have also shown that immediate administration of high doses of vitamin A (50,000-200,000 IUs) can help control the severity of the disease, particularly in children who are malnourished. In the United States, vitamin A treatment is often recommended for children hospitalized for measles, those who are immunocompromised, and for individuals found to be vitamin A deficit.

According the CDC, measles immunoglobulin can be administered within six days of measles exposure to high risk populations which include pregnant women without adequate blood titers for the prevention of measles, infants younger than one year of age, and persons with severe immunosuppression. Measles immunoglobulin may reduce the risk of infection and complications of measles; however, its use has been linked to degenerative diseases of cartilage and bone, sebaceous skin diseases, immunoreactive diseases, and tumors.

Antiviral agents such as ribavirin and interferon have also been used to treat measles in immunocompromised individuals, although there are outstanding questions about clinical efficacy.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

What is Measles vaccine?

Measles vaccine is a weakened (attenuated) form of the live measles virus. There are three vaccines currently available for use in the U.S. Two vaccines, Merck's MMRII and GlaxoSmithKline’s PRIORIX, contains Measles, Mumps and Rubella Vaccine, Live. Merck's ProQuad (MMRV) contains Measles, Mumps, Rubella and Varicella, Live.

Merck’s MMRII is licensed and recommended for individuals aged 12 months or older. It is a live attenuated virus vaccine propagated in chick embryo cells and cultured with Jeryl Lynn live attenuated virus mumps and Meruvax II, a live attenuated rubella virus vaccine propagated in WI-38 human diploid lung fibroblasts. The WI-38 human diploid cell line was derived from the lung tissue of a three-month human female embryo. The growth medium used was salt solution and 10 percent calf (bovine) serum.

Merck's ProQuad is licensed and recommended for individuals aged 12 months to 12 years of age. ProQuad (MMR-V -Measles, Mumps, Rubella and Varicella Virus Vaccine Live) is a combined, attenuated, live virus vaccine containing measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella viruses. ProQuad is a sterile lyophilized preparation of the components of M-M-R II (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Virus Vaccine Live): Measles Virus Vaccine Live, and Varicella Virus Vaccine Live (Oka/Merck), the Oka/Merck strain of varicella-zoster virus propagated in MRC-5 cells. MRC-5 cells are derived from a cell line developed in 1966 from lung tissue of a 14-week aborted fetus and contains viral antigens.

The growth medium for measles and mumps in both MMRII and ProQuad is a buffered salt solution containing vitamins and amino acids and it is supplemented with fetal bovine serum containing sucrose, phosphate, glutamate, recombinant human albumin, and neomycin. The growth medium for rubella is a buffered salt solution containing vitamins and amino acids and supplemented with fetal bovine serum containing recombinant human albumin and neomycin. Sorbitol and hydrolyzed gelatin stabilizer are added to the individual virus harvests. In the ProQuad vaccine, the Oka/Merck strain of the live attenuated varicella virus, initially obtained from a child with wild-type varicella, introduced into human embryonic lung cell cultures, adapted to and propagated in embryonic guinea pig cell cultures and human diploid cell cultures (WI-38), is then added to the MMRII component.

According to Merck, both MMRII and ProQuad vaccines are screened for adventitious agents. Each dose of MMRII contains sorbitol, sodium phosphate, sucrose, sodium chloride, hydrolyzed gelatin, recombinant human albumin, fetal bovine serum, other buffer and media ingredients and neomycin. Each dose of ProQuad contains sucrose, hydrolyzed gelatin, sorbitol, MSG, sodium phosphate, human albumin, sodium bicarbonate, potassium phosphate and chloride, neomycin, bovine calf serum, chick embryo cell culture, WI-38 human diploid lung fibroblasts and MRC-5 cells.

The MMRII vaccine product information insert states that the MMRII vaccine should be given one month before or one month after any other live viral vaccines. The ProQuad vaccine product information insert states that one month should lapse between administration of ProQuad and another measles containing vaccine such as MMRII and at least three months should lapse between ProQuad and any varicella containing vaccine.

GlaxoSmithKline’s PRIORIX is licensed and recommended for individuals aged 12 months or older. PRIORIX is made up of the Schwarz strain of live attenuated measles virus and the RIT 4385 strain of live attenuated mumps virus, derived from the Jeryl Lynn mumps strain, both propagated in chick-embryo fibroblasts. It also contains the Wistar RA 27/3 strain of live attenuated rubella virus propagated in MRC-5 human diploid cells.

These three virus strains are cultured in media containing amino acids, neomycin sulfate and bovine serum albumin. Multiple washings are done to remove the antibiotic and albumin from the media. The attenuated measles, mumps and rubella viruses are then mixed with a stabilizer before lyophilization. After reconstitution, the vaccine is a clear peach- to fuchsia pink-colored suspension. In addition to the measles, mumps, and rubella viruses, each 0.5ml dose also contains amino acids, mannitol, anhydrous lactose, and sorbitol. Each dose may also contain residual amounts of ovalbumin, bovine serum albumin and neomycin sulphate.

The tip caps of the prefilled syringes of diluent for PRIORIX contain natural rubber latex.

The CDC currently recommends that children receive two doses of a measles containing vaccine, with the first dose administered between 12-15 months, and the second dose between 4-6 years. The CDC also recommends that individuals born after 1957 and have no laboratory evidence of immunity or documentation of vaccination should receive at least one dose of MMR vaccine. Two doses of MMR vaccine are also recommended for healthcare personnel, students entering college and other post-high school educational institutions, and international travelers.

MMR vaccination is recommended by the CDC for infants between 6 and 11 months of age who may be traveling internationally; however, ProQuad MMRII and PRIORIX are only FDA approved for use in children 12 months and older. Both the MMRII and PRIORIX vaccine package insert states that the effectiveness and safety of the vaccines have not been established in children under 12 months. The MMRII package insert states that if administered to children 6 through 11 months, antibodies may not develop. According to the CDC, an infant vaccinated prior to 12 months of age will still require two additional doses of MMR vaccine.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about measles and the measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents, which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

What is the history of Measles vaccine in America and other countries?

The first two measles vaccines were initially licensed for use in the United States in 1963 and both contain the Edmonston B measles strain isolated by John Enders in 1954. Rubeovax, a live attenuated vaccine, was manufactured by Merck while Pfizer-Vax Measles-K, an inactivated (killed) virus vaccine, was manufactured by Pfizer.

At the time of vaccine approval, a single dose of the live attenuated Rubeovax was reported to be 95 percent effective at preventing measles, and protection from measles infection lasted at least three years and eight months. However, 30 to 40 percent of children who received Rubeovax experienced fever of 103 degrees or higher beginning on or around the sixth day following vaccination, lasting between 2 to 5 days. 30 to 60 percent of individuals who received Rubeovax also developed a “modified measles rash”. Due to the high number of side effects, public health and Merck officials recommended that Rubeovax be administered in conjunction with measles immune globulin, as co-administration significantly reduced vaccine reactions.

Pfizer-Vax Measles–K, Pfizer’s inactivated measles virus vaccine given in a series of three vaccines at one month intervals, was much less reactive but the vaccine offered limited effectiveness against the disease. In fact, the majority of children who received the vaccine had no detectable levels of measles antibodies when tested one year later.

By 1965, doctors were reporting of a new and abnormal measles-like illness (atypical measles) in children previously vaccinated with inactivated measles virus vaccine upon exposure to measles. Symptoms of atypical measles included rash, swelling, fever, pneumonia, and pleural effusion. Pfizer’s inactivated measles vaccine was removed from the market in 1968.

Prior to 1963, Enders permitted other vaccine researcher to work with the Edmonston measles strain in order to develop less reactive measles vaccines.

As a result, several additional live attenuated measles vaccines using the Edmonston B measles strain were also approved for use in 1963. These vaccines included M-Vac, manufactured by Lederle Pharmaceuticals, and various generic measles vaccines manufactured by pharmaceutical companies which included Parke Davis, Eli Lilly, and more. In addition to its inactivated measles vaccine, Pfizer also introduced Pfizer-Vax Measles-L, a live attenuated measles vaccine, in 1965.

By 1975, however, all previously FDA approved measles vaccines had been discontinued and replaced with two newer and more attenuated virus vaccines- Lirugen, manufactured by Pitman Moore-Dow, and Attenuvax, manufactured by Merck. Lirugen and Attenuvax were developed for use in the mid-1960s in response to the significant number of reported side effects from earlier live vaccines

Lirugen was developed from the Schwarz measles strain, a strain created by further attenuation of the Edmonston A measles strain. Lirugen was discontinued in the U.S. in 1976 but vaccines derived from the Schwarz measles strain remain in use outside the U.S.

Attenuvax live attenuated measles virus vaccine was developed from the Moraten measles strain, a strain created by further attenuation of the Edmonston B measles strain. Attenuvax was initially approved for use in the U.S. in 1968 and is currently found in both Merck’s Measles-Mumps-Rubella combination vaccine, MMRII, and in its Measles-Mumps-Rubella-Varicella vaccine, ProQuad (MMR-V).

In March 1967, public health officials announced that measles could be eradicated from the United States within a few months by use of the newly approved measles vaccines.

CDC officials published a paper in the medical literature describing measles virus as one that “has maintained a remarkably stable ecological relationship with man” and that measles “complications are infrequent.” They also reported that “with adequate medical care, fatality is rare” and that “immunity following recovery is solid and lifelong in duration.” Further, they stated that a 55 percent herd immunity threshold or more may be needed to prevent measles epidemics that cycle in communities every two to three years but that, “there is no reason to question that…the immune threshold is considerably less than 100 percent.”

However, mass vaccination of infants beginning at approximately one year of age and the push for all children entering school to receive a dose of measles vaccine did not result in measles eradication and outbreaks continued to occur in highly vaccinated populations.

By 1971, public health officials noted that measles outbreaks were on the rise and blamed the increasing number of measles cases on unvaccinated children and the lack of legislation in many states to require measles vaccination as a condition of school entry. Public health officials, however, acknowledged that vaccine failure played a role in outbreaks and blamed factors such as vaccination prior to 9 months of age, the use of measles gamma globulin, and improper vaccine handling and storage in addition to the vaccine’s 3 to 5 percent failure rate. The goal of measles eradication in the United States was no longer considered quickly achievable and researchers questioned whether it could be accomplished at all.

Measles outbreaks continued to occur throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s, impacting mainly pre-school and school aged children, many of whom had been appropriately vaccinated. Despite these continued outbreaks, in 1979, public health officials launched an effort to eliminate measles from the United States through vaccination, by October 1st, 1982. In 1982, there were a record low 1,697 reported measles cases in the United States and while public health officials admitted to failure, they publicly stated eradication to be “right around the corner”.

Measles cases decreased again in 1983, but in 1984, a thousand more cases were reported to the CDC. In 1985, nearly 300 additional cases of measles had been reported than the previous year, and of the 2,813 reported measles cases, 44 percent had occurred in appropriately vaccinated children.

Another measles resurgence occurred in 1989, and by the end of that year, 18,193 cases had been reported to the CDC, with over 40 percent of infections occurring in fully vaccinated individuals. The CDC blamed the outbreaks on both the failure of implementing vaccine programs, particularly those aimed at vaccinating preschool children, as well as on vaccine failure. While blaming the measles outbreaks on vaccine failure, the CDC continued to report a 95 percent measles vaccine effectiveness rate, all while denying that vaccine induced immunity was waning.

In 1989, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updated its measles vaccine recommendations and recommended that all children receive two doses of MMR vaccine prior to school entry, with the first dose at 15 months, and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, prior to school entry.

Also, in 1989, the CDC sponsored a study of two different measles vaccines on minority children living in the Los Angeles area. One of the measles vaccines used in the study was an unlicensed, experimental vaccine but the parents of children participating in the study were not made aware of this detail.

The experimental vaccine that was used was a high dose measles vaccine aimed at overwhelming the natural maternal antibodies which protect infants from infection during the first year of life. The presence of maternal antibodies at time of vaccination can lead to vaccine failure and the risk of measles infection later in life. While the vaccine had been in use outside of the country, by 1990, a high number of deaths in female children 6 months to 3 years after vaccination had been reported.

The study was halted in 1991 but the public was not informed of the study details until 1996. The CDC reported that no injuries or deaths occurred as a result of the use of the unlicensed, experimental vaccine; however, one child participant from the study died of a bacterial infection, which the CDC maintains to be unrelated to vaccination.

In 1998, concerns over safety of the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine surfaced following the publication of a case study involving 12 previously healthy children who developed severe gastrointestinal disorders after receiving the vaccine. Eight of the 12 children involved in the study also developed autism, with parents and personal physicians reporting symptom onset nearly immediately following MMR vaccine administration. The 13 physicians involved in the study also reported that they had investigated over 40 similar cases to the ones described in the published study. Study authors did not claim that the MMR vaccine was responsible for the gastrointestinal health problems but recommended for further research into the potential association.

Following publication, scientists involved in the study, including lead author Dr. Andrew Wakefield, a well-respected gastroenterologist practicing at the United Kingdom’s Royal Free hospital, became the target of public health officials and vaccine policymakers.

In late 2000, Wakefield and two contributing researchers, Dr. John Walker-Smith and Dr. Simon Murch, were brought up on charges of scientific misconduct by the UK’s General Medical Council (GMC) related to the published case study. Wakefield and Walker-Smith were found guilty in May 2010 and both physicians lost their medical licenses as a result.

Walker-Smith, however, appealed the verdict and in 2012, a U.K. high court reversed the decision. The presiding judge in the appeal case criticized the GMC’s disciplinary panel’s decision, and stated that "It would be a misfortune if this were to happen again.” Findings from the case study have been replicated; however, Wakefield continues to be a frequent target of the press and medical community.

In August 2014, William Thompson, a senior scientist at the CDC, came forward with allegations that CDC researchers purposely omitted data in 2004 in a study examining the MMR vaccine and autism among African American boys. According to Thompson, researchers involved in the 2004 study found a link between the MMR vaccine and autism in this population but chose to destroy the data.

After Thompson’s disclosure, Florida Senator Bill Posey called for an investigation of the CDC scientists involved in the study to determine whether fraud had been committed in an attempt to cover up a link between the MMR vaccine and autism.

Thompson’s allegations became the subject of Vaxxed: From Cover-Up to Catastrophe, a documentary first scheduled for debut at New York City’s Tribeca Film Festival in April 2016. The film, however, was dropped from the festival’s lineup after pressure and attacks by the media and others. As a result, the film’s first showing occurred at Manhattan’s Angelika Film Center on April 1, 2016. Government officials have yet to investigate the allegations brought forward by Thompson against his fellow CDC scientists.

In early January 2015, the CDC began investigating and outbreak of measles linked to California’s Disneyland theme park resort. In a statement released on January 23, 2015, the CDC announced that 51 confirmed cases of measles had been linked to the outbreak and encouraged MMR vaccination. Hundreds of measles outbreak news stories followed in the media, with many articles vilified parents of unvaccinated children while blaming them for the outbreak.

The Disneyland outbreak prompted several state legislators to introduce vaccine legislation aimed at eliminating or severely restricting religious and conscientious/philosophical vaccine exemptions. Vaccine choice advocates were highly successful in defeating many restrictive bills; however, California lost its personal belief exemption and Vermont lost its philosophical exemption but retained its religious vaccine exemption.

In 2015, only 188 cases of measles were reported in the U.S., a 72 percent decrease from the previous year. Of these cases, 147 were linked to the outbreak in California.

Measles increased again in January 2019, with outbreaks linked to travelers returning from countries such as the Philippines, Israel, and the Ukraine, where large outbreaks were ongoing. By mid-January, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced “vaccine hesitancy” to be one of the top ten global health threats and the U.S. government and media responded by launching an unprecedented response.

In Rockland County, New York, instead of quarantining people infected with measles, government officials threatened parents of healthy unvaccinated children with fines and imprisonment if their children appeared in public spaces – the first time ever in American history. Unvaccinated children and adults living, working or visiting in neighborhoods with certain zip codes in Brooklyn were threatened with steep fines if found in contact with someone with measles.

State legislatures, including Arizona, New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, Minnesota, Iowa, Alabama, Missouri, Maine, Massachusetts, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Wisconsin, were quick to introduce bills aimed at eliminating religious and conscientious/philosophical vaccine exemptions for school entry.

California introduced and amended a bill to severely restrict its medical exemption, by punishing doctors for writing exemptions and investigating schools with vaccine exemption rates lower than 95 percent.

Washington State passed a bill eliminating the philosophical exemption for the MMR vaccine, and Maine’s legislature voted to remove both its religious and philosophical exemption for all vaccines.

On June 13, 2019, the New York State legislature repealed its religious exemption to vaccination in one day, without permitting any public hearings.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) currently recommends that all children receive 2 doses of MMR vaccine. The first dose is recommended at 12-15 months and the second dose at 4 to 6 years, prior to school entry.

Measles vaccination rates remain high in the U.S. In 2017, the CDC reported that 94 percent of children entering kindergarten had received two doses of MMR vaccine. For the 2018-2019 school year, 94.7 percent of children in kindergarten had received the two recommended doses of MMR vaccine.

Further, in 2020, 92.4 percent of adolescents 13 to 17 years were reported to have received the two recommended MMR vaccine doses.

In June 2022, the FDA approved PRIORIX, a live attenuated measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline. PRIORIX was initially licensed in Germany in 1997 and according to the CDC, the vaccine has been in use globally in nearly 100 countries. On June 23, 2022, the CDC’s ACIP voted to approve use of PRIORIX as an option for the MMR vaccine according to the current MMR recommendations and off-label uses.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

How effective is Measles vaccine?

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that measles antibodies develop in approximately 95 percent of children vaccinated at 12 months and 98 percent of children vaccinated at 15 months or older. It is estimated that about 2-5 percent of children, who receive the vaccine at 12 months of age or younger or who only receive a single dose of MMR, fail to be protected. A second dose of MMR is thought to stimulate a protective immune response in about 99 percent of vaccine recipients.

From 1963, when the measles vaccine was first introduced in the United States, until December of 1989, public health officials recommended that all children receive a single dose of measles vaccine beginning at 12 months of age.

During this time, however, measles cases and outbreaks occurred among vaccinated children. In 1973, Dr. Stanley Plotkin warned that vaccinated children could still get measles and that “a history of previous vaccination cannot be assumed to exclude measles as the cause of an exanthum rash, whether typical or atypical.” He said that, “about 5 percent of vacinees do not respond and presumably remain susceptible,” which he described as “primary vaccine failures.”

Dr. Plotkin also stated that there was evidence that some previously vaccinated children exposed to wild type measles could “develop modified illness and a secondary type of antibody response,” which he described as “secondary vaccine failures.”

By 1982, researchers had discovered that infants vaccinated in the first year of life were not protected from measles, even after repeated vaccine doses.

From 1985 to 1988, there were between 55 and 110 measles outbreaks every year in the U.S., primarily in highly vaccinated school-aged populations. Measles swept through a middle school in Texas, where 99 percent of the students were vaccinated, and in a Massachusetts high school with a 98 percent vaccination rate.

In 1989, measles cases exploded in North and Central America, including in the U.S. and were associated with unusually high morbidity and mortality. CDC officials did not explain the increases but insisted that “measles vaccines appear to be as effective today as in the past.” They did, however, state that “analysis of contemporary strains of measles virus suggest that circulating viruses may have changed somewhat from past strains.”

In 1998, CDC officials confirmed that the 1989-1990 measles outbreak, which caused a higher number of hospitalizations and deaths, was associated with circulation of Group 2 measles viruses, particularly D3, that were “genetically distinct from vaccine strains.”

More than 45,000 measles cases and over 100 deaths were reported in the U.S. during 1989 and 1990. Numerous outbreaks were reported among vaccinated school children but a large number of cases also occurred in babies less than 15 months old and in unvaccinated toddlers, as well as in college students. Approximately 80 percent of affected school children were found to be appropriately vaccinated.

In December of 1989, the CDC recommended that children should receive their first dose of MMR vaccine at 15 months and all children should get a booster dose before entering kindergarten. “When fully implemented,” CDC officials stated, “this schedule should lead to the elimination of measles among school aged children and college students.” They also reported that “Although the titers of vaccine-induced antibodies are lower than those following natural disease, both serologic and epidemiologic evidence indicate that vaccine-induced protection appears to be long lasting in most individuals.”

Published medical research, however, indicates that vaccine failure due to waning immunity can occur, despite multiple doses of measles vaccine. Measles vaccine acquired immunity is reported to wane in at least five percent of cases, within 10 to 15 years after vaccination. Moreover, exposure to natural measles may be necessary for the maintenance of protective antibodies in vaccinated persons.

The Vaccine Research Group at Minnesota’s Mayo Clinic reports that up to 10 percent of persons who receive two doses of MMR vaccine “fail to develop protective humoral immunity and those antibody levels wane over time, which can result in infection.” Further, they admit that “While the current vaccine used in the USA and many other countries is safe and effective, paradoxically in the unique case of measles, it appears to insufficiently induce herd immunity in the population.”

Mayo Clinic researchers have also found that individuals respond differently to vaccination and each individual’s genes play a role in controlling measles vaccine-induced immune responses. They report that scientists still do not completely understand “how the immune response is generated” or “how host genetic and epigenetic variations change and impact vaccine immune responses,” or “how pathogens interact with the immune system.” They also state that “The importance of cellular immunity to vaccine-induced protection is not completely understood.” Some children with no detectible measles antibodies may still be protected against measles, which supports the “involvement of cellular immunity.”

Further, they admit that scientists do not currently have “a detailed understanding of the pathogenesis of the measles virus” or of vaccine-induced innate and adaptive (humoral) immunity and that better correlates of protection “that go beyond measuring antibody titers” are needed. There is not enough information about what drives a vaccine response, a vaccine non-response, adverse events following vaccination and the many complex interactions between immune function-related components known at this time.

Genetic ancestry may also play a significant role in measles vaccine responses. One cohort study found that Caucasians and most Hispanics, ethnic groups which represent nearly 80 percent of the U.S. population, showed significantly lower humoral and cellular responses to MMR vaccination than African Americans.

Scientists are also questioning the MMR vaccine’s ability to completely protect against the currently circulating measles strains. In 2017, microbiologists from India reported that “The measles virus (MeV) is serologically monotypic but genotyping confirms eight clades (A-H). The clades are further subdivided into 23 genotypes….Although sera from vaccinated individuals neutralize all the clades, the efficacy varies from clade to clade. It may be said that thelevel of protection offered by this vaccine varies from genotype to genotype.”

Further, they stated that “The present vaccine does not offer complete protection assurance and the limitations are evident now. Newer strains show epitopes that are not shared by vaccine strains. Variations in the efficacy of neutralization in the vaccinated individuals against wild MeV has been reported.”

In the past 2 decades, waning immunity resulting in both asymptomatic and modified clinical illness has been documented in the medical literature.

In 1998, CDC officials acknowledged that:

“Mild or asymptomatic measles infections are probably very common among measles-immune persons exposed to measles cases and may be the most common manifestation of measles during outbreaks in highly immune populations.”

German virologists confirmed the results and reported that:

“…measles virus (MV) could circulate in seropositive fully protected populations. Among individuals fully protected against disease, those prone to asymptomatic secondary immune response are the most likely to support subclinical MV transmission.”

In 1999, European researchers found that “…a substantial proportion of individuals who respond to measles vaccine display an antibody boost accompanied by mild or no symptoms on exposure to wild virus” and in highly vaccinated populations “neutralizing antibodies are decaying significantly in absence of circulating virus.” They estimated “the mean duration of vaccine induced protection in absence of re-exposure to be 25 years,” warning that, “there is a need to establish the intensity and duration of infectiousness in vaccinated individuals.”

In 2002, Japanese researchers reported that “measles virus can infect previously immune individuals,” both those who are naturally immune and those who have been vaccinated, and that the reinfection can produce “a wide range of illnesses: typical measles, mild modified measles and asymptomatic infection.” Researchers concluded that, “…the number of cases of measles among previously immunized individuals has increased, probably caused by waning of vaccine-induced immunity” and suggested that “…asymptomatic measles infections occur even in the adult population with unexpectedly high frequency and this supports the preservation of measles immunity.”

The number of vaccinated people infected with measles and who show few or no symptoms but transmit measles to others is also unknown as vaccinated individuals are not routinely surveyed to determine whether they are experiencing asymptomatic or atypical measles and transmitting it to other.

In June 2018, Japanese researchers reporting on an outbreak of measles in Japan between March and May 2018, concluded that “… the vaccinated population may play a role in the transmission dynamics of measles – probably due to secondary vaccination failure (waning of vaccine-induced immunity to non-protective levels).”

In May 2019, Australian scientists reported evidence of “waning measles immunity among vaccinated individuals” that is “associated with secondary vaccine failure and modified clinical illness” with “transmission potential.”

This finding confirmed the scientific evidence from Germany in April 2019 which reported:

“Although measles cases have gradually declined globally since the 1980s together with an increase in vaccination coverage, there has been a resurgence of measles in the European Union and European Economic Area starting in 2017 with adults aged over 20 years comprising more than a third of all cases.”

“The impact of waning immunity to measles will likely become more apparent over the coming years and may increase in the future, as the vaccinated population (with hardly any exposure to measles) will grow older and the time since vaccination increases. It is worth noting that the median age of measles cases has been increasing over the past 15 years in Berlin and the extent of waning immunity may increase further. Vaccinated cases have a lower viraemia and have rarely been observed to contribute to transmission. However, with the vaccinated population turning older and titres possibly decreasing further, this observation has to be re-evaluated.”

In the past decade, outbreaks of measles in highly vaccinated populations have been documented in medical literature.

In 2011, a fully vaccinated person transmitted measles to four contacts, of which two contacts had documentation of receiving two prior MMR doses and two had confirmed blood antibody results considered protective against measles.

In 2014, an outbreak of measles occurred among vaccinated health care workers in the Netherlands. Of the eight confirmed cases, six had received two measles vaccines, one had received a single dose, and one worker was unvaccinated. Study authors concluded that among the 106 potentially exposed health care workers, the effectiveness of two doses of measles vaccine were approximately 52 percent.

In 2017, an outbreak of measles occurred among young soldiers in Israel. The primary patient involved in the outbreak had documentation of having received three doses of measles vaccine and the additional eight cases of measles were found to have occurred in persons who reported having, or provided documentation of having, at least two doses of a measles containing vaccine.

A 2016 published study conducted by the CDC, FDA, and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health found that the use of a third dose of MMR vaccine in an attempt to boost antibodies in persons with low measles antibodies was not effective.

Merck’s MMRII product information insert states that if infants born to mothers who have experienced natural measles infection are vaccinated at less than one year of age, they may not develop long lasting vaccine acquired antibodies. Natural maternal measles antibodies interfere with the vaccine’s ability to produce antibodies, which may result in vaccine failure.

Additional research on maternal measles antibodies concluded that infants born to mothers who were vaccinated against measles have lower levels of maternal antibodies and lost them sooner in comparison to infants born to naturally immune mothers. As a result, most infants younger than 12 months who are born to measles vaccinated mothers “lack both passive and active immunity, leaving them unprotected and in the highest-risk group for life-threatening complications.”

In June 2022, the FDA and CDC approved use of PRIORIX, a live attenuated measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine, for individuals 12 months of age and old. The effectiveness of PRIORIX was based on antibody responses when compared to the MMRII vaccine and according to the package insert, PRIORIX was considered non-inferior to Merck’s MMRII vaccine.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Measles and the Measles vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Can Measles vaccine cause injury & death?

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) report minor side effects from the MMR-V and MMR vaccines to include low-grade fever, injection site redness or rash, pain at the injection site, and facial swelling. Moderate side effects include a full body rash, temporary low platelet count, temporary stiffness and pain at the joints, and seizures. A vaccine strain infection following vaccination may be the cause of the full body rash.

There is a significantly greater risk of seizures following MMR-V vaccine in comparison to separate administrations of MMR and varicella vaccines if the MMR-V is given as the first dose of the series.

Rare serious side effects of both MMR-V and MMR include seizures, life-threatening infection, severe allergic reaction, and death.

Serious complications reported by Merck in the MMR-V (ProQuad) product insert during vaccine post-marketing surveillance have included:

- measles;

- atypical measles;

- vaccine strain varicella;

- varicella-like rash;

- herpes zoster;

- herpes simplex;

- pneumonia and respiratory infection;

- pneumonitis;

- bronchitis;

- epididymitis;

- cellulitis;

- skin infection;

- subacute sclerosing panencephalitis;

- aseptic meningitis;

- thrombocytopenia;

- aplastic anemia (anemia due to the bone marrow’s inability to produce platelets, red and white blood cells);

- lymphadenitis (inflammation of the lymph nodes);

- anaphylaxis including related symptoms of peripheral, angioneurotic and facial edema;

- agitation;

- ocular palsies;

- necrotizing retinitis (inflammation of the eye);

- nerve deafness;

- optic and retrobulbar neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve);

- Bell’s palsy (sudden but temporary weakness of one half of the face);

- cerebrovascular accident (stroke);

- acute disseminated encephalomyelitis;

- measles inclusion body encephalitis;

- transverse myelitis;

- encephalopathy;

- Guillain-Barre Syndrome;

- syncope (fainting);

- tremor;

- dizziness;

- paraesthesia;

- febrile seizure;

- afebrile seizures or convulsions;

- polyneuropathy (dysfunction of numerous peripheral nerves of the body);

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome;

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura;

- acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy;

- erythema multiforme;

- panniculitis;

- arthritis;

- death

A 2014 published study on the MMR-V vaccine in Canada found that the risk of febrile seizures to be double in children receiving the MMR-V vaccine in comparison to those receiving separate doses of MMR and varicella vaccines. A 2015 meta-analysis found a two-fold increase in febrile seizures between 5 and 12 days or 7 and 10 days following MMR-V vaccination in children between the ages of 10 and 24 months.

MMR-V vaccine contains albumin, a human blood derivative, and as a result, a theoretical risk of contamination with Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) exists. Merck states that no cases of transmission of CJD or other viral diseases have been identified and virus pools, cells, bovine serum, and human albumin used in vaccine manufacturing are all tested to assure the final product is free of potentially harmful agents.

Serious complications reported by Merck in the MMRIIproduct insert during vaccine post-marketing surveillance have included:

- brain inflammation (encephalitis) and encephalopathy (chronic brain dysfunction);

- panniculitis (inflammation of the fat layer under the skin);

- atypical measles;

- syncope (sudden loss of consciousness, fainting);

- vasculitis (inflammation of the blood vessels);

- pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas);

- diabetes mellitus;

- thrombocytopenia purpura (blood disorder);

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura (inflammation and bleeding in the small blood vessels);

- acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (rare vasculitis of the skin’s small vessels occurring in infants);

- leukocytosis (high white blood cell count);

- anaphylaxis (shock);

- bronchial spasms;

- pneumonia;

- pneumonitis(inflammation of the lung tissues);

- arthritis and arthralgia (joint pain);

- myalgia (muscle pain);

- polyneuritis (inflammation of several nerves simultaneously);

- measles inclusion body encephalitis (disease affecting the brain of immunocompromised persons);

- subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (fatal progressive brain disorder thought to be caused by exposure to the measles virus);

- Guillain-Barre Syndrome (disease where the body’s immune system attacks the nerves);

- acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM- brief widespread inflammation of the nerve’s protective covering);

- transverse myelitis (inflammation of the spinal cord);

- aseptic meningitis;

- erythema multiforme (skin disorder from an allergic reaction or infection);

- urticarial rash (hives, itching from an allergic reaction);

- measles-like rash;

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome (severe reaction causing the skin and mucous membranes to blister, die, and shed);

- nerve deafness (hearing loss from damage to the inner ear);

- otitis media (ear infection);

- retinitis (inflammation of the retina of the eye);

- optic neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve);

- conjunctivitis (pink eye);

- ocular palsies (dysfunction of the ocular nerve);

- epididymitis (inflammation of the epididymis);

- paresthesia (burning or prickling of the skin);

- death.

Serious complications reported by GlaxoSmithKline in the PRIORIX package insert during vaccine post-marketing surveillance have included:

- Vasculitis (including Henoch-Schönlein purpura and Kawasaki syndrome);

- Thrombocytopenia and thrombocytopenic purpura;

- Anaphylactic reactions;

- Meningitis;

- “Mumps like” illness;

- “Measles like” illness;

- Orchitis;

- Epididymitis;

- Parotitis;

- Erythema multiforme;

- Arthralgia;

- Arthritis;

- Encephalitis;

- Cerebellitis;

- Cerebellitis-like symptoms (including transient gait disturbance and transient ataxia);

- Guillain-Barré syndrome;

- Transverse myelitis;

- Peripheral neuritis;

- Afebrile seizures;

In the comprehensive report evaluating scientific evidence, Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality, published in 2012 by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), 30 reported vaccine adverse events following the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine were evaluated by a physician committee. These adverse events included measles inclusion body encephalitis, febrile seizures, arthritis, meningitis, Guillain-Barre Syndrome, autism, diabetes mellitus, optic neuritis, transverse myelitis and more.

In 23 of the 30 measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine-related adverse events evaluated, the IOM committee concluded that there was inadequate evidence to support or reject a causal relationship between the MMR vaccine and the reported adverse event, primarily because there was either an absence of methodologically sound published studies or too few quality studies to make a determination.

The IOM committee, however, concluded that the scientific evidence “convincingly supports” a causal relationship between febrile seizures, anaphylaxis, and measles inclusion body encephalitis in immunocompromised individuals and the MMR vaccine and favored acceptance of a causal relationship between transient arthralgia in both children and women and the MMR vaccine. After reviewing only five epidemiological studies, the IOM committee concluded that it favored rejection of a causal association between both autism and Type 1 diabetes and the MMR vaccine.

In 2012, the Cochrane Collaborative examined 57 studies and clinical trials involving approximately 14.7 million children who had received the MMR vaccine. While the study authors stated that they were not able to detect a “significant” association between MMR vaccine and autism, asthma, leukemia, hay fever, type I diabetes, gait disturbance, Crohn’s disease, demyelinating diseases or bacterial or viral infections, they reported that “The design and reporting of safety outcomes in MMR vaccine studies, both pre- and post-marketing, are largely inadequate.”

In an updated review published in April of 2020, the Cochrane Collaborative reviewed 87 safety studies associated with MMR, MMR-V, and MMR + Varicella vaccine. This review concluded that there was an association between MMR vaccines containing Leningrad-Zagreb and Urabe mumps strains and aseptic meningitis, but no evidence to support this association for MMR vaccines which contain the Jeryl Lynn mumps strains. This conclusion was based on the evaluation of nine studies, all of which were considered low certainty studies. The Cochrane Collaborative reports low certainty studies to be those where their “confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.”

An association was also found between MMR vaccines and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and MMR, MMR-V, and MMR + Varicella vaccines and febrile seizures and the studies evaluated to make this determination were a combination of both moderate certainty and low certainty studies. Moderate certainty studies are those in which the Cochrane Collaborative are “moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.”

The Cochrane Collaborative reported that no association was found between MMR vaccine and encephalitis, encephalopathy, cognitive delay, type 1 diabetes, asthma, dermatitis/eczema, hay fever, leukemia, multiple sclerosis, gait disturbance, and bacterial or viral infections; however, all the studies that were evaluated were found to be either low certainty or very low certainty studies. Very low certainty studies are those in which the Collaborative have “very little confidence in the effect estimate” and that “the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.”

No association was found between autism spectrum disorders and MMR vaccines, and the studies evaluated were a combination of moderate certainty and low certainty studies. The Cochrane Collaborative also reported that there was insufficient evidence to support or reject an association between MMR vaccines and inflammatory bowel disease.

As of March 29, 2024, there have been 112,733 reports of measles-vaccine reactions, hospitalizations, injuries, and deaths following measles vaccinations made to the federal Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS), including 560 related deaths, 8,639 hospitalizations, and 2,162 related disabilities. However, the numbers of vaccine-related injuries and deaths reported to VAERS may not reflect the true number of serious health problems that occur after measles vaccination.

Even though the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 legally required pediatricians and other vaccine providers to report serious health problems following vaccination to federal health agencies (VAERS), many doctors and other medical workers giving vaccines to children and adults fail to report vaccine-related health problem to VAERS. There is evidence that only between 1 and 10 percent of serious health problems that occur after use of prescription drugs or vaccines in the U.S. are ever reported to federal health officials who are responsible for regulating the safety of drugs and vaccines and issue national vaccine policy recommendations.

As of April 1, 2024, there have been 1,367 claims filed in the federal Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) for 85 deaths and 1,282 injuries that occurred after measles vaccination. Of that number, the U.S. Court of Claims administering the VICP has compensated 526 children and adults, who have filed claims for measles vaccine injury.

One example of an MMR vaccine injury claim awarded compensation in the VICP is the case of O.R. On February 13, 2013, O.R. received the MMR, Haemophilus Influenzae type B (Hib), Pneumococcal (Prevnar 13), Hepatitis A, and Varicella vaccines. That evening following vaccination, she became feverish and irritable, which prompted her mother to contact the doctor. The doctor advised O.R.’s mom to administer Benadryl and Tylenol for her symptoms. The fever persisted for several days and was followed by a severe seizure resulting in cardiac and respiratory arrest. The cardiac arrest and seizure caused O.R. to develop encephalopathy, kidney failure, severe brain injury, low muscle tone and cortical vision impairment. After several months of inpatient hospitalization, O.R. was discharged home with 24-hour supervised medical care. On November 20, 2017, the court conceded that the MMR vaccine caused her encephalopathy and O.R. was awarded a $101 million-dollar settlement to cover medical expenses for the rest of her life.

In 1998, public health officials and attorneys associated with the federal Vaccine Injury Compensation Program published a review in Pediatrics in regard to the medical records of 48 children ages 10 to 49 months, who received a measles vaccine or combination MMR vaccine between 1970 and 1993 and developed encephalopathy after vaccination. The children either died or were left with permanent brain dysfunction, including developmental regression and delays, chronic seizures, motor and sensory deficits and movement disorders. The study authors concluded that: