Read and report vaccine reactions, harassment and failures.

Pneumococcal: The Disease

Pneumococcal disease is an infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) bacteria. Only a few of the serotypes cause the majority of pneumococcal infections but nearly all serotypes have the ability to cause serious disease. S. pneumoniae are frequently found in the respiratory tract and up to 90 percent of healthy people may have the bacteria present in the nasopharynx (upper area of the throat behind the nose). Between 20 and 60 percent of all school children may also carry the bacteria.

Most pneumococcal infections are mild, however, serious illness can occur. S. pneumoniae can cause several types of infections, including pneumonia, ear infections, sinus infections, bloodstream infections (bacteremia) and meningitis. Less commonly, S. pneumoniae can cause bacterial bone and joint infections, pericarditis, endocarditis, and peritonitis. Learn more about Pneumococcal…

Pneumococcal Vaccine

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has approved two different pneumococcal containing shots. There are different rules for use of these vaccines by different aged groups.

Prevnar 13 is a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) manufactured by Wyeth (Pfizer) pharmaceuticals, containing Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F and 23F. Prevnar 13 does not protect against infection and disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae strains not present in the vaccine. Prevnar 13 is approved for varying uses in children, teenagers and adults.

PNEUMOVAX23 is a pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV) manufactured by Merck and contains Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A,12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19F, 19A, 20, 22F, 23F, and 33F. Pneumovax 23 does not protect against infection and disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae strains not present in the vaccine. PNEUMOVAX23 is approved for use in adults 50 years of age or older and in children 2 and older who are at increased risk for pneumococcal disease. Learn more about Pneumococcal vaccine…

Pneumococcal Quick Facts

Pneumococcal

- Symptoms of pneumococcal infection include sudden onset of fever and fatigue, sneezing and cough with mucus and shortness of breath. The infection may start with a general feeling of being unwell, a low-grade fever and a cough that doesn’t include mucus before symptoms worsen. Symptoms of pneumococcal meningitis (brain inflammation) include stiff neck (inability to touch the chin to chest without moderate to severe pain in the back of the neck and head); headache; extreme fatigue or seizures. Symptoms of otitis media include a painful ear, red or swollen eardrum, fever, and irritability.

- Pneumococcal bacteria are primarily transmitted through respiratory secretions by coughing and sneezing. Persons most at risk of developing invasive pneumococcal disease include immunocompromised individuals, smokers, persons with chronic cardiac, lung, or kidney disease, individuals without a spleen, and persons with cochlear implants or a cerebrospinal fluid leak. Children attending daycare are also at a higher risk. Continue reading quick facts…

Pneumococcal Vaccine

- The CDC recommends four doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) for infants and children, with a dose given at 2, 4, 6 and between 12 and 18 months of age. Children between 2 and 18 years who are at a higher risk of invasive pneumococcal disease are also recommended to receive one dose of PPSV23 at least 8 weeks following the most recent dose of PCV13. A second dose of PPSV23 is recommended at least 5 years following the first dose in children who are immunocompromised, HIV-positive, have sickle cell disease, or who lack a functioning spleen. PPSV23 and PCV13 are also recommended for use in immunocompromised children, adults, and seniors.

- All adults 65 years of age and older are recommended by the CDC to receive one dose of PPSV23. PCV13 can also be considered for use in healthy seniors 65 years and older but routine vaccination is no longer recommended. This recommendation was revised at the June 2019 Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) when data presented found limited benefit to vaccinating all seniors with PCV13 vaccine. Continue reading quick facts…

NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents below, which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

What is Pneumococcal?

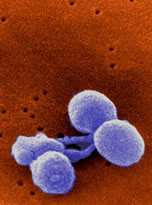

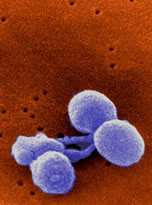

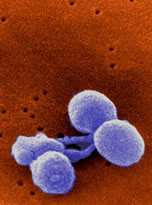

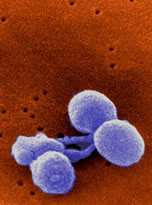

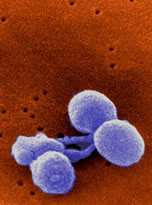

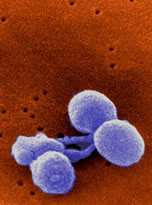

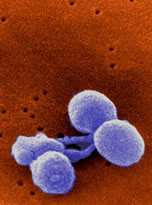

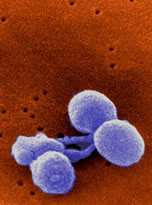

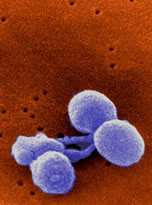

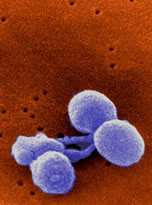

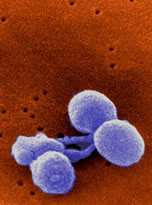

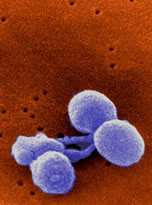

Pneumococcal disease is an infection caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) bacteria. S. pneumoniae bacteria are gram-positive, lancet shaped, facultative anaerobic bacteria and currently over 90 known serotypes have been identified. Only a few of the serotypes cause the majority of pneumococcal infections but nearly all serotypes have the ability to cause serious disease.

S. pneumoniae are frequently found in the respiratory tract and up to 90 percent of healthy people may have the bacteria present in the nasopharynx (upper area of the throat behind the nose). Between 20 and 60 percent of all school children may also carry the bacteria. Colonization of S. pneumoniae in the nasopharynx tends to be the greatest at age 3 and declines thereafter. S. pneumoniae colonization in adults is generally acquired by exposure children, however the rates found in adults are lower than those seen in children.Most pneumococcal infections are mild, however, serious illness can occur. S. pneumoniae can cause several types of infections, including pneumonia, ear infections, sinus infections, bloodstream infections (bacteremia) and meningitis. Less commonly, S. pneumoniae can cause bacterial bone and joint infections, pericarditis, endocarditis, and peritonitis.

In adults, pneumococcal pneumonia is the most common form of pneumococcal disease. The incubation period of pneumococcal pneumonia is between 1 and 3 days and its initial symptoms of chills, rigors, and fever often occur abruptly. Other symptoms include a productive cough, rapid heart rate and breathing, shortness of breath, poor oxygenation, rust colored sputum, weakness, and malaise. Headache, vomiting, and nausea may occur as well, although less frequently.

Pneumococcal bacteremia without pneumonia is another form of pneumococcal disease and symptoms include chills, fever, and a lower level of consciousness. An estimated 5,000 cases of pneumococcal bacteremia occur yearly in the United States.

Pneumococcal meningitis accounts for over 50 percent of all cases of bacterial meningitis in the United States. Symptoms of meningitis may include fever, stiff neck, irritability, vomiting, seizures, headache, light sensitivity, and coma. Between 3,000 and 6,000 cases of pneumococcal meningitis occur yearly in the United States and death occurs in approximately 22 percent of adults and 8 percent of children.

In children, acute otitis media (middle ear infection) is the most common form of pneumococcal disease and S. pneumoniae can be found in up to 55 percent of ear aspirates. Before the age of one, over 60 percent of children will have at least one middle ear infection. Otitis media results in more medical office visits than any other childhood illness. Symptoms of pneumococcal otitis media (middle ear infection) in children include fussiness, tugging at ears, sleeplessness, hearing difficulties, and balance issues. In some children, ear infections can become chronic, resulting in recurrent antibiotic use or surgery to place tubes in the ears.

Lab testing of blood or other body fluids such as cerebrospinal fluid, must be completed to confirm a diagnosis of S. pneumoniae.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Is Pneumococcal contagious?

S. pneumoniae, the bacteria which causes pneumococcal disease, is contagious and is spread through coughing, sneezing or direct contact with respiratory secretions. The exact period of communicability of pneumococcal disease is not known, however, it is generally believed that as long as the strain remains present in the respiratory secretions, it has the capacity to be transmitted to others. One study suggests that S. pneumoniae bacteria may exist on the surfaces of commonly handled objects for some time (minutes to no more than three days), raising the possibility of direct infection.

Pneumococcal infections are more common during the winter and in early spring when respiratory diseases are more prevalent. Outbreaks of pneumococcal disease are not common, but the risk of an outbreak is increased in environments where a lot of people are enclosed in crowded spaces. Environments where pneumococcal disease is more likely to spread include nursing homes, residential housing facilities, orphanages, and daycare centers.

People, especially children, often have pneumococcal bacteria present in their nose or throat at some time or another without any clinical illness. This is referred to as “carriage.” It is still not known why carriage only rarely leads to clinical illness.

Infection, however, occurs most often after acquiring a new pneumococcal strain, and studies have shown that 15 percent of children who acquire a new strain become ill with acute otitis media or another type of pneumococcal disease within one month of acquiring the strain.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

What is the history of Pneumococcal in America and other countries?

Streptococcus pneumoniae was first isolated independently in 1880, both in France, by Louis Pasteur, and in the United States, by Dr. George M. Sternberg, a U.S. Army physician. In the mid-1880s, an association between S. pneumoniae and lobar pneumonia was described in medical literature and in 1884, the discovery of the Gram Stain helped to distinguish the bacteria from other forms of pneumonia. During this decade, researchers also discovered that S. pneumoniae could cause meningitis.

At the turn of the 20th century, physicians became more aware of pneumococcus, its relationship to pneumonia, and the increasing mortality rates associated with it. Published papers began to appear in medical journals detailing the impact of pneumonia in the United States. In 1900, pneumonia (and influenza) was the leading cause of infectious disease death and the third leading cause of overall death in the U.S.

Research continued and by 1909, Ludwig Handel and Franz Neufeld of the Robert Koch Institute for Infectious Diseases in Berlin, developed a technique to categorize the different strains of pneumococci. Between 1915 and 1945, a great deal of research focused on further understanding the structure of the S. pneumoniae bacteria, its ability to cause disease, and the impact of disease on humans. By 1940, more than 80 types of S. pneumoniae had been identified and described.

S. pneumoniae was noted to be genetically diverse and identifiable by its unique outer capsule surrounding the bacteria. The capsule was found to be crucial in maintaining the pneumococci’s ability to cause infection by preventing other cells from devouring it, in a process known as phagocytosis. The prevalence of a particular serotype was found to be dependent on geographical location, characteristics of the infected person, and the use of antibiotics and vaccines.Changes in the prevalence of a particular S. pneumoniae serotype within a population were also noted to have occurred throughout its history and S. pneumoniae was determined to frequently transform through a process known as recombination, or capsular switching. In this process, the bacterial cell incorporates DNA from other closely related bacteria into its own genome, enabling it to adapt, and allowing it to resist antibiotics or evade vaccines.

As treatment of pneumococcal disease impacted the transformation of S. pneumoniae, medical interventions targeting the infection have been critical to its history. Early research into treatment options against the disease began nearly immediately after the bacteria’s identification.

One of the first antimicrobials to be studied as a possible treatment against pneumococcal disease was a quinine derivative known as optochin. Optochin, however, was found to have a narrow window of effectiveness between toxic and therapeutic doses. The development of Optochin as a potential treatment of S. pneumoniae was discontinued quickly due to the risk of toxicity.

The next treatment of S. pneumoniae involved the use of antiserum derived first from animals (rabbits and horses) then from humans. During the 1930s and 40s, human antiserum was considered the primary treatment option for pneumococcal pneumonia. During this time, treatment of the individual patient evolved into a “community” responsibility, and pneumonia became one of the leading health concerns in the U.S.

The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, which had lost over $24 million dollars in death benefits in the wake of the 1918-1919 Spanish influenza, led as the largest campaign contributor in the fight against this respiratory disease. In 1937, it joined with the U.S. Health Service to produce a 12 minute film on pneumococcal pneumonia, which debuted at New York City’s famous Radio City Music Hall. Pneumococcal pneumonia was declared a national health emergency which required a coordinated effort between the public, physicians, and health agencies in order to advance and promote medical treatments to target the disease.

By 1940, approximately two thirds of the U.S. states and territories in would develop pneumonia-control programs and federal funding for pneumococcal increased nearly 60-fold in three years. In 1940, pneumonia and influenza was reported to be the fifth leading cause of infectious disease death in the U.S, and was reported to occur at a rate of 70.3 cases per 100,000 people.

During this era, a new pneumococcal treatment option became available in the form of an antimicrobial compound known as sulfapyridine. When published research noted its ability to reduce pneumococcal disease mortality rates, it quickly became the most popular treatment option against the disease. Its use increased even further when it was found to have successfully treated Sir Winston Churchill’s bacterial pneumonia.

The success of sulfapyridine, and eventually penicillin, against pneumococcal pneumonia resulted in a decline in the use of human antiserum and by the late 1940s, all pneumococcal control programs had been discontinued.

By the mid-1940s, penicillin had become more readily available and found to be highly effective against numerous infectious diseases, including pneumococcal disease. Penicillin quickly became recognized as one of the most effective treatments against S. pneumoniae associated infections. While several pneumococcal vaccines were developed for use between 1909 and the mid-1940s, the discovery of penicillin as an effective treatment and the preference of its use by doctors, resulted in limited use of these products.

The discovery of antimicrobials and antibiotics which were found to effectively treat a number of different infections, including S. pneumoniae, prompted a change in pneumococcal treatment protocols. The culturing and typing of infections were no longer routinely performed by clinicians, with many preferring to administer antibiotics for nearly any clinical sign of infection. Some clinicians believed that treating all infections prophylactically with antibiotics would be the safest and most effective way to prevent pneumococcal disease and others chose to prescribe antibiotics at the first sign of any illness.

By the early 1960s, pneumonia researchers, expressing concern over the indiscriminate use of antibiotic, reported that only 10 percent of all persons prescribed antibiotics actually required them. Sulfa resistant strains of S. pneumoniae had already been noted in the 1940s and by the 1960s, penicillin resistant strains had begun to emerge.

Concerns over antibiotic treatment failures and death rates resulting from invasive pneumococcal disease in the 1960s prompted a renewed interest in pneumococcal vaccination development; however, it took researchers until the early 1980s to publish papers suggesting that the overuse of unnecessary antibiotics may be responsible for the increasing number of antibiotic-resistant strains of infection, suggesting that this practice be curtailed. Despite published literature, the scientific community did not sound the alarm over the rise in antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria until the mid-1990s. By 1998, 24 percent of pneumococcal strains were found to be resistant to penicillin and 14 percent of strains were noted to be resistant to multiple antibiotics.

30 percent of all invasive S. pneumoniae infections are currently resistant to one or more antibiotics, with resistance noted to be dependent on geographical location. Adults over 65 and children under 5 are most likely to harbor antibiotic resistant strains of S. pneumoniae.

Antibiotic resistance pushed pneumococcal disease back into the public health spotlight and the need for new treatment approaches has been identified as a priority by both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Over 90 strains of S. pneumoniae have been identified with 10 strains found to cause approximately 62 percent of all cases of invasive pneumococcal disease globally. In the U.S., 80 percent of invasive pneumococcal disease found in children 6 and under is the result of 7 common strains. In 2017, there were 16,620 reported cases of invasive pneumococcal disease in the U.S and 1,220 of those cases occurred in children under 5.

Global disease

WHO estimates S. pneumoniae to be responsible for the death of half a million children worldwide every year. The majority of these deaths occur in developing countries located in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. As with pneumococcal disease in the U.S., older adults and young children are most susceptible to infection, and only a small number of strains are responsible for the majority of infections.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Can Pneumococcal cause injury and/or death?

Although most pneumococcal infections are mild, pneumococcal disease can cause serious illness. The 3 most common illnesses caused by invasive S. pneumoniae include pneumonia, meningitis, and bacteremia; however, S. pneumoniae can also cause other rare but serious pneumococcal infections including peritonitis, endocarditis and pericarditis, and infection of the bones and joints (septic arthritis, osteomyelitis).

S. pneumoniae can also cause middle ear infections, conjunctivitis, and sinus infections but these infections are generally mild and rarely result in complications. S. pneumoniae can also cause a worsening of symptoms in someone with chronic bronchitis.

The most common serious form of pneumococcal disease is pneumonia. Symptoms of infection may include rapid or difficulty breathing, chest pain, chills, fever, and cough. Older adults may also experience altered levels of alertness and confusion. Complications of pneumococcal pneumonia include pericarditis, airway obstruction, empyema, lung abscess, lung collapse, and death. Between 5 and 7 percent of persons with pneumococcal pneumonia die from the illness and elderly patients are most at risk of death.

Since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, pneumococcal empyema, a complication of pneumococcal pneumonia which causes pus to accumulate between the lungs and the inner aspect of the chest wall, has become more common. S. pneumoniae strains noted to cause this complication include serotype 1, 3, and 19A.

S. pneumoniae can also cause an infection of the blood, known as bacteremia. Initial symptoms of bacteremia may include a lower level of alertness, fever, and chills. Symptoms of sepsis, a serious complication of bacteremia, often include severe pain, sweaty or clammy skin, difficulty breathing, elevated heartrate, and confusion. Sepsis can lead to organ failure, tissue damage, and death.

Pneumococcal meningitis, an infection of the lining of the spinal cord and brain, can also be cause by S. pneumoniae. Symptoms of infection often include sensitivity to light, headache, fever, neck stiffness, and confusion. In infants, symptoms may include a reduced level of alertness, lack of appetite, poor fluid intake, and vomiting. Complications of pneumococcal meningitis include developmental delays, hearing loss, and death.

Pneumococcal peritonitis, an infection of the lining of the walls of the abdomen and pelvis, is another rare but serious form of invasive pneumococcal disease. Pneumococcal peritonitis is more commonly found in persons with cirrhosis of the liver, HIV, and hepatitis C. but can also be the result of severe pelvic inflammatory disease, gastrointestinal ulcer or injury, or malignancy. Symptoms of infection often include diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, and dehydration.

Pneumococcal endocarditis and pericarditis are 2 rare but serious heart infections. Symptoms of pneumococcal pericarditis often include fever, fatigue, chest pain which can radiate to the back, neck, abdomen or shoulder, cough, swelling of the extremities, and muffled heart sounds. Symptoms of pneumococcal endocarditis often include joint and/or muscle pain, fever, anorexia, sweating, and new or changing heart murmurs.

In rare cases, S. pneumoniae can cause septic arthritis and osteomyelitis (bone infection). Symptoms of septic arthritis include hot, swollen, or painful joints and frequently involve the knees or ankles. Half of all persons who develop pneumococcal septic arthritis will also have osteomyelitis. Symptoms of osteomyelitis often include redness, warmth, and swelling to the infected area, fever, chills, pain, and children may show signs of lethargy or irritability.

S. pneumoniae accounts for up to 50 percent of middle ear infections (otitis media). Symptoms of otitis media often include fever, a red or swollen ear drum, ear pain, and sleepiness. Ear and sinus infections are generally mild; however, children who develop frequent ear infections may require ear tube placement.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Who is at highest risk for getting Pneumococcal?

Pneumococcal disease can affect anyone; however, some people may be at a greater risk for the disease. Risk factors include age and certain pre-existing medical conditions. Approximately 90 percent of invasive pneumococcal disease occurs in adults. Adults considered most at risk of illness are persons 65 and older.

Persons between the age of 19 and 64 considered at highrisk of pneumococcal disease include:

- Smokers

- Chronic alcoholics

- Persons with chronic illness such as lung, heart, kidney, or liver disease

- Individuals with asthma

- Diabetics

- Persons who are immunocompromised (ie HIV positive)

- Individuals with cancer

- Persons without a functioning spleen

- Individuals with a cochlear implant or cerebrospinal leak

- Persons living in a nursing home, group home, or other long-term care facility.

Adults with living with chronic diseases such as diabetes, COPD, and chronic heart disease are at risk for developing invasive pneumococcal disease at any time during the year.

Children considered most at risk for developing invasive pneumococcal disease include young children under 2 and those who attend child care in a group setting. Additionally, Children with cochlear implants or cerebrospinal fluid leaks, chronic lung, health, kidney, or liver disease, sickle cell disease, and those with immunocompromising conditions are also consider to be at high risk for invasive disease.

African Americans, Alaskan Natives, and certain American Native groups have been found to have higher rates of pneumococcal disease.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Who is at highest risk for suffering complications from Pneumococcal?

Individuals with chronic illnesses such as COPD, asthma, diabetes, and heart disease are at higher risk of acquiring pneumococcal disease and suffering from complications related to the disease. Further, inhaled medications (corticosteroids and anti-cholinergics) used to treat these medical conditions increases both the risk of invasive pneumococcal disease and the risk of complications and death from the illness.

The risk of respiratory and cardiac complications—both of which are associated with increased mortality—is greater in individuals with chronic lung and/or heart diseases. Additional risk factors of mortality after hospitalization for invasive pneumococcal disease include:

- coexisting chronic conditions

- re-hospitalization within 30 days of hospital discharge, and

- Residing in a nursing home.

In adults hospitalized for invasive pneumococcal disease, risk factors for respiratory failure included:

- Age of 50 years and older

- Chronic lung disease

- Coronary heart disease, and

- Infection with serotype 3, 19A or 19F.

Current smokers hospitalized with pneumococcal pneumonia have a five-fold increased risk of 30-day mortality from the disease when compared with non-smokers and ex-smokers.

Five and a half percent of non-hospitalized children will develop long-term major respiratory consequences from pneumonia of any type and the risk is three times higher among children hospitalized with disease.

One out of 100 children younger than five with bacteremia or sepsis (blood infection) will die from it. The risk of death from pneumococcal bacteremia is also higher among elderly people. It is estimated that one out of every 15 children under five who develop pneumococcal meningitis will die from the infection.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Can Pneumococcal be prevented and are there treatment options?

Illnesses that can be spread by respiratory secretions can also be prevented by:

- Washing hands thoroughly or using hand sanitizer when handwashing is not available

- Staying home when ill

- Staying home when you have been exposed to illness and may be contagious

- Using a tissue when sneezing or coughing

If invasive pneumococcal disease, such as pneumonia, meningitis or bacteremia infection is suspected, blood or cerebrospinal fluid should be collected for testing. Identification and confirmation of the specific bacteria is important as it allows clinicians to select the most appropriate antibiotic to decrease the risk of severe infection. Non-invasive pneumococcal pneumonia in adults can be diagnosed by a simple rapid urine test. This test can also help in the selection of antibiotics for treatment.

Ear and sinus infections are usually diagnosed based on health history and physical examination. As there are multiple strains of S. pneumoniae, it is often difficult to determine which strain is responsible for a given infection, or which antibiotic will be most effective. Over-prescription of ineffective antibiotics has contributed to the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.

The treatment of invasive pneumococcal infection usually begins with the use of an antibiotic that can target a number of different strains of bacteria. When lab results confirm the type of bacteria, a more selective and targeted antibiotic may be used instead. Oral antibiotics are prescribed for mild infections, however, more serious infections require antibiotics to be administered intravenously. In some cases, hospitalization will be required due to the severity of this illness. Many types of bacteria, including pneumococcal bacteria, have become resistant to antibiotics as a direct result of overuse and misuse of antibiotics.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

What is Pneumococcal vaccine?

NVIC strongly recommends reading the vaccine manufacturer product information insert before you or your child receives any vaccine, including pneumococcal vaccine. Product inserts are published by drug companies making vaccines and list important information about vaccine ingredients, reported health problems (adverse events) associated with the vaccine, and directions for who should and should not get the vaccine.

Links to the pneumococcal vaccine product inserts are available below or you can ask your doctor to give you a copy of the vaccine product insert to read before you or your child is vaccinated. It is best to ask your doctor for a copy of the product inserts for the vaccines you or your child is scheduled to receive well in advance of the vaccination appointment.

Pneumococcal Vaccines Licensed for Use in the U.S.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has approved two different pneumococcal containing shots. There are different rules for use of these vaccines by different aged groups. Links to the pneumococcal vaccine package insert can be located on the pneumococcal disease Quick Facts page.

Prevnar 13 is a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) manufactured by Wyeth (Pfizer) pharmaceuticals, containing Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F and 23F. Prevnar 13 does not protect against infection and disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae strains not present in the vaccine.

Prevnar 13 is approved for the following uses:

- In children between the ages of six weeks and five years of age for the prevention of invasive disease and otitis media;

- In children and teenagers between the ages of six and seventeen years of age for the prevention of invasive disease;

- In adults eighteen years of age and older for the prevention of pneumonia and invasive disease.

Prevnar 13 is a 13-valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine containing Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, and 23F, each individually linked to non-toxic diphtheria CRM197 protein. Serotypes are each grown in a soy peptone broth and each polysaccharide is purified. Each polysaccharide is then chemically activated to make saccharide and linked to the Diphtheria CRM197 protein to form the glycoconjugate. CRM197, a nontoxic variant of diphtheria toxin, is isolated from cultures of Corynebacterium diphtheria strain C7 which has been grown in a yeast extract and casamino acids based medium or in a chemically-defined medium. CRM197 and each glycoconjugate is then purified and the individual glycoconjugates are joined to make Prevnar 13. Each 0.5ml dose of Prevnar 13 contains approximately 2.2 μg of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, 23F saccharides, 4.4 μg of 6B saccharides, 34 μg CRM197 carrier protein, 295 μg succinate buffer, 100 μg polysorbate 80, and 125 μg aluminum as aluminum phosphate adjuvant.

PNEUMOVAX23 is a pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV) manufactured by Merck and contains Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A,12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19F, 19A, 20, 22F, 23F, and 33F. Pneumovax 23 does not protect against infection and disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae strains not present in the vaccine.

PNEUMOVAX23 is approved for use in adults 50 years of age or older and in children 2 and older who are at increased risk for pneumococcal disease.

PNEUMOVAX23 is a polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine and contains a mixture of purified capsular polysaccharides comprised of Streptococcus pneumoniae types 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19F, 19A, 20, 22F, 23F, and 33F. PNEUMOVAX 23 is a clear, colorless and sterile solution and each 0.5-mL dose of vaccine contains 25 micrograms of each type of polysaccharide in an isotonic saline solution containing 0.25% phenol as a preservative.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

What is the history of Pneumococcal vaccine use in America?

The earliest known pneumococcal vaccines in the United States date back to 1909 in the form of heat-treated, whole-cell vaccines. These early vaccines remained available for use until the mid-1930s, with several of these products containing additional vaccines aimed at preventing illnesses caused by Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella, Neisseria catarrhalis, and more.

The first pneumococcal vaccine trials began in South Africa in 1911 and involved miners who were administered a whole-cell vaccine consisting of the known circulating strains of pneumococcal. The results of this first study were improperly recorded and as a result, a second trial of a similarly formulated vaccine was initiated in the summer of 1912. This second vaccine was reported to offer some protection from pneumonia but this protection lasted only about 2 months. Further, while vaccination appeared to slightly reduce pneumonia rate, it had no impact on pneumonia death rates.

A third trial which involved a similar pneumococcal vaccine was reported by investigators to decrease pneumonia rates by 25 to 50 percent and death rates by 40 to 50 percent. Sir Almroth Knight, the primary researcher involved in the first 3 clinical trials, however, paid no attention to the strains of pneumonia used within the vaccines, making the overall effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccination difficult to determine.

Sir F. Spencer Lister, a protégé of Sir Almroth Knight, expanded on Knight’s earlier work by developing a system to identify and type different strains of pneumococcal. Lister noted the presence of unique pneumococcal strains not found in North America and Europe.

In 1914, Lister developed the first whole-cell pneumococcal vaccine containing three specific strains of S. pneumoniae, now known as serotypes 1, 2, and 5. Lister’s vaccine trials involved the administration of 3 vaccine doses given 1 week apart to miners working at 3 different South African mines. All 3 mines experienced a decrease in pneumococcal morbidity and mortality in the six to twelve month period of observation post-vaccination.

By 1918, Lister expanded on his vaccine by adding five additional pneumococcal strains and planned to administer this vaccine to all South African miners. However, by the mid- 1920s, his vaccine was found to be ineffective. By the early 1930s, pneumonia caused by strains 1, 2, 5, and 7, four strains targeted by his vaccine, remained low; however pneumonia rates from strain 3, a strain also found in his vaccine, were noted to be three times higher among those who received the vaccine.

During the First World War, 2 U.S. military bases began pneumococcal vaccination campaigns and troops were vaccinated with a pneumococcal vaccine containing strains 1, 2, and 3. Vaccination was found to reduce the rates of pneumonia caused by the strains specific to the vaccine but vaccine recipients were studied for a period of only 2 to 3 months and the long-term effectiveness of the vaccine was never determined.

Pneumococcal vaccines were also administered in several setting during the 1918 flu pandemic, including military bases, with mixed effectiveness. Vaccines administered during this period also included strains of additional bacteria, such as B. influenza, Staphylococcus aureus, or hemolytic streptococci.

Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides were discovered in 1916-1917, but it took researchers until 1927 to realize that the polysaccharides could induce an immune response. The first pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine contained pneumococcal strain 1 and strain 2, and the vaccine was administered to nearly 120,000 Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) men in the 1930s as part of several clinical trial studies. The vaccine’s effectiveness was studies for only a few months and no long-term studies were ever completed.

In 1937, a polysaccharide vaccine containing pneumococcal strain (serotype) 1 was used during a pneumonia outbreak at an adult psychiatric hospital. This trial reported that the vaccine significantly decreased pneumonia rates.

Both military and civilian clinical trials of polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccines reported favorable results, and in 1947, the first pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine licenses were granted to E.R. Squibb & Sons. Squibb’s adult vaccine contained serotypes 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 and 8 while its pediatric vaccine contained serotypes 1, 4, 6, 14, 18 and 19.

Use of these vaccines were short-lived as doctors preferred to use newly discovered antibiotics to treat pneumonia. Production of polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccines ended in 1951 and in 1954, Squibb withdrew its vaccine license due to lack of demand for the product.

Pneumococcal vaccine development resumed again in 1968, this time at the insistence of National Institutes of Health (NIH) scientist Dr. Robert Austrian. Austrian had witnessed numerous antibiotic treatment failures in the clinical setting and believed pneumococcal disease rates to be much higher than reported related to a significant decrease in the use of testing to confirm a diagnosis.

Eli Lilly & Co was granted a contract by the NIH to research and develop an effective pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. In 1972, vaccine trials of Eli Lilly’s pneumococcal vaccine began in South Africa; however, by 1975, Eli Lilly had terminated its research and development after several issues with the vaccine had occurred.

Meanwhile, Merck Sharp and Dohme, with knowledge and experience related to the research and development of a meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine for the United States Army in the late 1960s, had already started on a pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine development by 1970.Merck also chose to complete pneumococcal vaccine clinical trials in South Africa and reported that their 6 and 12-valent vaccines reduced pneumococcal pneumonia disease rates by 76 and 92 percent respectively.

Merck applied for a license to manufacture and market a 14-valent pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine, PNEUMOVAX, in 1976 and received FDA approval for the vaccine on November 21, 1977. In January 1978, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended that the new pneumococcal vaccine be administered to all children and adults 2 and older with chronic health conditions which included sickle cell anemia, splenic dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, and chronic renal, lung, liver, and kidney disease. The vaccine was also approved for use during a pneumococcal outbreak involving a closed population, such as a nursing home or similar institution.

Lederle, another established vaccine manufacturer, had also begun the research and development of a pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in the 1970s and in August 1979, PNU-IMUNE, its 14-valent pneumococcal vaccine, received FDA approval.

By the early 1980s, pneumococcal experts recognized the need to expand the number of pneumococcal strains contained within the polysaccharide vaccine to improve coverage on a global scale. The World Health Organization (WHO) along with the governments of several countries, reported that a 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine would provide better protection against pneumococcal disease worldwide.

In 1983, both Merck and Lederle introduced pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines (PPV23) containing 23 strains of pneumococcal which were believed to cause approximately 87 percent of all bacterial pneumonia cases in the United States. The PPV23 vaccines were reformulated to contain 25mcg of each specific antigen, a decrease from the 50mcg per antigen found in the 14-valent vaccine, in an attempt to better balance safety and immune response.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted in 1984 to recommend that all adults 65 and older receive a dose of PPV23 vaccine. This recommendation was made despite knowing that 2 separate studies had found the vaccine to be ineffective in reducing pneumococcal infections and deaths. ACIP also continued to recommend that all adults and children 2 and older with chronic illness or immunosuppression receive a dose of the vaccine.

In 1997, PPV23 recommendations were updated to include special populations such as individuals living in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities and for use in Alaskan Natives and certain American Indians populations.

As pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines were found to be ineffective in children under the age of 2, vaccine development continued. Pneumococcal related deaths were reported to be uncommon among children except in the case of immune suppression, meningitis, or severe bacteremia following the removal of the spleen, but children 2 and under along with adults 65 and older, were still considered by health officials to be at a higher risk for pneumococcal infections.

Development of a method to bind a polysaccharide with a carrier protein to enhance the immune response began in 1980, and in 1987, the conjugated Hib vaccine became the first vaccine using polysaccharide-protein conjugation technology to receive approval by the FDA.

Wyeth Lederle was the first vaccine manufacturer to develop a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. In pre-licensing clinical trials, Prevnar 7 (PCV7) was tested against an experimental meningitis C vaccine, which seriously compromised the scientific validity of the trial. The vaccine, however, still received approval by the FDA in February of 2000.

The 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine contained Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F individually conjugated to diphtheria CRM197 protein and was approved for use in infants and children at 2, 4, 6, and 12-15 months of age for the prevention of invasive disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae from the strains found within the vaccine.

On June 21st, 2000, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to recommend PCV7 vaccine for use in all children 23 months of age and younger, as well as in children ages 24 to 59 months considered to be at high-risk of serious pneumococcal infection.

The highly successful promotion by Wyeth Lederle, the CDC, and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) made Prevnar (PCV7) the best-selling new pharmaceutical product of 2000, generating $461 million in sales.

By 2001, however, PCV7’s popularity, in conjunction with manufacturing issues, resulted in vaccine shortages. The shortages required ACIP to temporarily revise PCV7 vaccine recommendations, prioritizing the vaccine’s use in children most at risk for pneumococcal disease. Issues with vaccine shortages were not completely resolved until September of 2004.

In October 2002, the FDA approved PCV7 for use in the prevention of middle ear infections (otitis media) despite clinical studies noting the vaccine to be only 7 percent effective against all types of acute otitis media.

Following PCV7 introduction on a global scale, scientists began to report that while the vaccine appeared to be effective in reducing nasopharyngeal carriage of S. pneumoniae strains found within the vaccine, this reduction had resulted in a significant increase in non-vaccine type strains, most notably, strain 19A, a highly virulent and antibiotic-resistant serotype. In Spain, an increase in invasive pneumococcal disease occurred following the introduction of PCV7, with the emergence of several non-vaccine type strains.

Vaccine manufacturers responded to the emergence of multiple antibiotic-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae by introducing new pneumococcal vaccines containing additional strains. In March 2009, Synflorix (PCV10), a 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, containing three additional strains not found in PCV7 (1, 5, and 7F) received approval for use in Europe. One year later, in February of 2010, Wyeth pharmaceuticals received approval for Prevnar 13 (PCV13) vaccine, a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, which added 6 additional strains (1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F, and 19A) to the original Prevnar (PCV) vaccine.

Recommendations for the use of PCV13 were issued promptly by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) which essentially recommended that PCV13 be used in lieu of PCV7. Prior to FDA approval PCV13 was studied for safety in less than 4,800 healthy infants and toddlers and the vaccine was compared to infants and children receiving PCV7, alone or in combination with other vaccines.

ACIP also recommended PCV13 for children and teenagers between 6 and 18 years of age not previously vaccinated and considered to be at high risk for pneumococcal disease related to immunosuppressive conditions including sickle cell anemia, asplenia, HIV, the presence of a cochlear implant, or cerebrospinal fluid leak. At the time of this recommendation in December of 2010, the FDA had not approved the vaccine for use in children over the age of 59 months and did not expand the usage of PCV13 vaccine for children and teenagers between the ages of 6 and 17 until January of 2013.

In December of 2011, the FDA approved the expanded use of PCV13 under an “Accelerated Approval” process to include adults 50 years of age and older. The “Accelerated Approval” process allows products targeted to treat a serious condition or fill an unmet need the opportunity to receive quicker FDA approval based on laboratory tests or other measurements believed to possibly predict a clinical benefit.

In this case, a comparison was made between antibody responses of individuals receiving either PCV13 or Merck’s 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). PCV 13 was found to have a similar or higher antibody response when compared to PPSV23 and the FDA permitted this laboratory finding to fulfill the requirement needed to receive “Accelerated Approval”, despite knowing that the level of vaccine-induced antibodies required to protect an individual against a particular strain of pneumococcal infection is unknown.

While the ACIP declined to routinely recommend PCV13 for adults over the age of 50 following the FDA’s approval to expand its usage, the committee did vote to recommend the vaccine for use in immunocompromised adults 19 years of age and older, in June of 2012. The FDA, however, did not approve PCV13 for use in adults 19 to 49 until July 11, 2016.

In 2014, ACIP updated its recommendations for the use of PCV13, recommending the vaccine be administered to all seniors 65 and older in addition to the previously recommended PPSV23 vaccine; however, by October 2018, ACIP reported that is recommendation had not reduced pneumonia rates among persons 65 years and older.

In June 2019, ACIP voted to pull back from its 2014 recommendation and stated that healthy seniors 65 and older could consider this vaccination after discussions with their physician. PCV13 is still recommended for seniors 65 years and older who have chronic health conditions and a single dose of PPSV23 is still recommended for all persons 65 and older.

Since the introduction of PCV13, pneumococcal strains not covered within the vaccine have continued to emerge. Researchers in the United States have noted that while invasive pneumococcal disease has decreased since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, S. pneumoniae strains have adapted and antibiotic resistant non-vaccine strains have emerged. These non-vaccine type strains include strains 33F, 22F, 12, 15B, 15C, and 23 A.

Korea, Taiwan, and several Western European countries, have also reported an increase in pneumococcal strains not covered by PCV13 and scientists continue to recommend pneumococcal strain monitoring and further development of vaccines in response to continued emergence of non-vaccine type strains.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

How effective is Pneumococcal vaccine?

PPSV23 Vaccine Effectiveness

The initial pre-licensing clinical trials of a pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide involved a comparison study of the effectiveness of a 6-valent polysaccharide vaccine against a 12-valent polysaccharide vaccine. The study involved South African gold miners between the ages of 16 and 58, a population noted to be at a higher risk for pneumococcal pneumonia. The 6-valent vaccine was reported to be 76 percent effective while the 12-valent vaccine was found to be 92 percent effective against the particular pneumococcal strains found in the vaccine.

The long-term effectiveness of the vaccine was not measured as the study was limited to only one year. An additional polysaccharide vaccine effectiveness study involving both a 6-valent and 13-valent polysaccharide vaccine found a 79 percent reduction in pneumococcal pneumonia and an 82 percent reduction in pneumococcal bacteremia caused by the strains found in the vaccine.

In the United States, two post-licensing trials on the effectiveness of the original 14-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in the elderly or persons with chronic medical conditions found the vaccine to be ineffective against bronchitis and pneumonia in this particular population.

Additional research on the effectiveness of the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine based on the CDC’s pneumococcal surveillance system found the vaccine to be 57 percent effective against the serotypes found within PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) in persons 6 and older, between 65 and 84 percent effective in persons with chronic illness (ie diabetes, congestive heart failure, COPD, etc), and 75 percent effective in healthy persons 65 and older. Vaccine effectiveness, however, could not be determined in certain populations of individuals with immunosuppressive conditions.

When PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) was administered in combination with ZOSTAVAX, Merck’s live attenuated shingles vaccine, shingles antibody levels were found to be significantly lower when compared to administering the shingles vaccine four weeks after PNEUMOVAX23 administration.

A 2008 study found that while PPSV23 reduced the risk of invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly by 38 percent, it had no impact on pneumonia rates. In 2010, researchers found the vaccine to be completely ineffective at reducing the rates of hospitalization or death in persons previously treated for community acquired pneumonia. The vaccine was also found to be ineffective in both transplant patients, and persons with HIV who had low CD4+ cell counts and did not reduce the rates of pneumonia in persons with rheumatoid arthritis.

PCV 13 Vaccine Effectiveness

Information on pneumococcal conjugate vaccine efficacy found in the Prevnar 13(PCV13) product insert reports information pertaining to the original PCV vaccine, Prevnar (PCV7). PCV7 was reported to be 100 percent effective at preventing invasive disease caused by S. pneumoniae during the pre-licensing clinical trial which took place over a 34 month period. An eight month extended follow-up of vaccine recipients reported the vaccine’s efficacy to be between 93 and 97.4 percent effective.

In clinical studies pertaining to the PCV vaccine for the prevention of acute otitis media, studies found PCV7 to be only 7 percent effective at preventing acute otitis media and children who received PCV7 were noted to be at a higher risk for developing acute otitis media from strains not covered by the vaccine. Studies also found that PCV7 reduced the need for tympanostomy tubes (ear tubes) by only about 20 percent.

One large scale study involving nearly 85,000 adults 65 and older found PCV13 to be 45.6 percent effective against vaccine-type pneumococcal pneumonia, 45 percent effective against vaccine-type non-bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia and 75 percent effective against all vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease.

The Prevnar 13(PCV13) product insert also states that effectiveness of the vaccine cannot be established in the following population:

- Infants born prematurely

- Persons with HIV-infection

- Children with sickle cell disease

- Persons who had received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant

Following FDA approval of the first pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, Prevnar (PCV7), researchers discovered that while the vaccine was effective in reducing the risk of infection caused by the 7 strains found within the vaccine, strains not found within the vaccine began to increase. Most notably, strain 19A, a highly virulent strain resistant to all antibiotics FDA approved for use in children for the treatment of acute otitis media, emerged.

In addition to pneumococcal strain replacement, the introduction of PCV7 resulted in a significant increase in pneumococcal empyema, a complication of pneumococcal pneumonia resulting in an accumulation of pus between the lungs and the inner aspect of the chest wall. The most common strains causing empyema were found to be pneumococcal strains 1, 3 and 19A, three strains not covered in the PCV7 vaccine.

While invasive disease from vaccine-type strains decreased significantly within the first four years following the introduction of PCV7, antibiotic resistant non-vaccine type strains began to take their place. In one particular population of Alaska Native children, the introduction of the PCV7 vaccine caused a 140 percent increase of invasive pneumococcal disease from strains not found in the vaccine.

Rates of pneumococcal meningitis by antibiotic resistant strains not found in the PCV7 vaccine continued to increase, which prompted researchers to emphasize the need for better pneumococcal vaccines.

The 2010 introduction of PCV13 vaccine, adding six additional strains to the original PCV7, resulted in a further decline of invasive pneumococcal disease. However, PCV 13 vaccine has not been completely effective in eliminating vaccine-strain invasive pneumococcal disease and serious infections have persisted despite the licensing of a broader targeting vaccine.

In addition to the vaccine’s ineffectiveness in eliminating pneumococcal disease from all strains contained within the vaccine, non-vaccine type strains have also emerged in the United States, most notably strains 33F, 22F, 12, 15B, 15C, and 23 A. Other countries have experienced a similar situation, including Taiwan, which noted a decrease in vaccine-type strain invasive disease and confirmed pneumococcal disease but an increase in non-vaccine type strain invasive disease, most notably caused by strains 23A, 15A and 15B.

Korea has also reported high rates of antibiotic-resistant strains not found in PCV13 since the introduction of the vaccine. Non-vaccine type strains continue to appear in many Western European countries, prompting researchers stress the need for new vaccines to cover the antibiotic-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae not found within the current vaccines.

Researchers in the United States have noted that while invasive pneumococcal disease has decreased since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, S. pneumoniae strains have continued to adapt and this has resulted in the ongoing emergence of antibiotic resistant non-vaccine serotypes.

The use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines has also caused an increase in other serious pathogens such as Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Since the introduction of PCV vaccines, H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis otitis media have increased to replace S.pneumoniae otitis media.

While the CDC and other global health organizations have attributed the decrease in invasive pneumococcal disease to vaccination, the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines has brought changes to clinical practice. Emergency room collection of blood cultures, once a routine practice in the assessment and treatment of children presenting with fever in the emergency room, have decreased since PCV vaccine introduction. This change in clinical treatment protocol may be artificially inflating the rate of decrease of pneumococcal disease in children and reducing the detection of non-vaccine type replacement strains.

A study of Aboriginals living in Western Australia found that while PCV7 vaccination decreased the number of vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal infections in the elderly and young children, it significantly increased the amount of non-vaccine type pneumococcal diseases in adults.

Another study involving a similar population in Australia found that vaccine strains of pneumococcal were not replaced by non-vaccine strain infections in children but non-vaccine strain infections rose significantly in adults. This offset any potential benefit that vaccination might have had on the adult population.

At the CDC’s October 2018 ACIP meeting, public health officials that vaccinating all persons 65 and older with PCV13 has had no impact on reducing the rates of both invasive and non-invasive pneumococcal disease. In June 2019, ACIP voted to pull back from its 2014 recommendation and stated that healthy seniors 65 and older could consider this vaccination after discussions with their physician. PCV13 is still recommended for seniors 65 years and older who have chronic health conditions and a single dose of PPSV23 is still recommended for all persons 65 and older.

The continued emergence of non-vaccine type pneumococcal strains has resulted in the development of new pneumococcal vaccines. Merck is currently in stage 3 clinical trials of a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, which will add strain 22F and 33F to the 13 strains currently found in PCV13.

Pfizer was recently awarded Breakthrough Therapy Designation by the FDA for a new 20-valent pneumococcal vaccine. Breakthrough Therapy Designation allows drug companies the opportunity “to expedite the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition and preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy on a clinically significant endpoint(s).”

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Can Pneumococcal vaccine cause injury & death?

According to the CDC, problems that may result following vaccination with PCV13, PPSV23, and any other vaccine include:

- Severe allergic reactions occurring within a few minutes or a few hours of vaccination

- Severe shoulder pain limiting the movement in the arm where administration occurred.

- Fainting or collapse following vaccination. It may be advised to sit or lie down for approximately 15 minutes following vaccination to prevent fainting and injuries that could result from a fall. It is important to notify your health care provider if you have ringing in the ears, visual changes, or dizziness following vaccination.

PCV13 vaccine side-effects (Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine)

Adverse reactions following administration of PCV13 differed by dose in the series and age of the recipient. In children, the most commonly reported reactions included irritability, drowsiness, loss of appetite, redness, pain, or swelling to the vaccine site, and mild or moderate fever.

Children who received PCV13 at the same time as the inactivated influenza vaccine were noted to be at a higher risk for febrile seizures.

In adults, injection site redness, swelling, and pain, fatigue, fever, chills, headache, and muscle pain were most commonly reported.

Prevnar 13 (PCV13) adverse reactions reported in infants and young children during pre-licensing clinical trials: injection site pain, swelling, redness, fever, decreased appetite, increased and decreased sleep, irritability, diarrhea, vomiting, rash, hives, hypersensitivity reaction including bronchospasm, facial swelling, and shortness of breath, seizures, pneumonia, gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis, and death (reported as SIDS).

Prevnar 13 (PCV13) adverse reactions reported in adults during pre-licensing clinical trials: Injection site pain, swelling, and redness, limited arm movement, fever, vomiting, chills, muscle pain, fatigue, headache, decreased appetite, rash, joint pain, and death (deaths reported in the pre-licensing clinical trials included deaths from cancer, cardiac disorders, peritonitis, Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary infection, and septic shock.)

Prevnar 13 (PCV13) adverse reactions reported post-marketing: Cyanosis, lymphadenopathy at the injection site, anaphylaxis, shock, hypotonia, pallor, apnea, angioneurotic edema, erythema multiforme, injection site itching, hives, and rash.

Pre-licensing clinical trials of the first pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, Prevnar (PCV7), compared the safety of Prevnar (PCV7) against an experimental meningitis C vaccine, seriously compromising the scientific validity of the trial.

In pre-licensing clinical trials of Prevnar (PCV7), children in groups who received the pneumococcal vaccine suffered more seizures, irritability, high fevers and other reactions. There were 12 deaths in the Prevnar (PCV7) group, including 5 Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) deaths. No long term studies were completed to evaluate whether Prevnar (PCV7) vaccine given alone or in combination with other vaccines had any association with chronic illness or disabilities, such as the development of diabetes, asthma, seizure disorders, learning disabilities, ADHD, or autism.

Pre-licensing clinical safety trials of Prevnar 13 (PCV13) compared this next generation vaccine against the original Prevnar (PCV7) vaccine, a vaccine inadequately studied for safety and by 2012, concerns regarding a link between febrile seizure and Prevnar 13(PCV13) had been reported.

PCV13 was found to be associated with an elevated risk of febrile seizures when administered independently as well as when given in combination with the inactivated injected influenza vaccine (IIV). The CDC continues to encourage simultaneous vaccine of both PCV13 and IIV vaccines despite knowledge of an increased risk of seizures in children.

Studies have also linked PCV vaccine to Guillain-Barre Syndrome, polyserositis, septic shoulder and erythema multiforme.

PPSV23 vaccine side-effects (Pneumococcal Polysaccharide)

According to the CDC, approximately 50 percent of individuals who receive the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) experience pain and redness at the injection site. Muscles aches, fever, and more severe localized reactions can also occur following administration of PPSV23.

PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) adverse reactions reported in adults during pre-licensing clinical trials: injection site pain, redness, itching, bruising and swelling, headache, chills, fever, diarrhea, dyspepsia, nausea, upper respiratory infection, back pain, neck pain, pharyngitis, muscle pain, fatigue, depression, ulcerative colitis, chest pain, angina pectoris, heart failure, tremor, stiffness, sweating, stroke, lumbar radiculopathy, pancreatitis, myocardial infarction, and death.

Nearly 80 percent of individuals participating in pre-licensing clinical trials experienced an injection-site adverse reaction following revaccination at three to five years following the initial vaccine. The rate of systemic adverse reactions (headache, fatigue, myalgia) following revaccination with PPSV23 was also higher with 33 percent of adults aged 65 and older and 37.5 percent of adults between 50 and 64 reporting an adverse reaction.

PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) adverse reactions reported post-marketing: Anaphylactoid reactions, serum sickness, angioneurotic edema, arthritis, arthralgia, vomiting, nausea, decreased limb mobility, peripheral edema in the limb where injection occurred, fever, malaise, cellulitis, injection site warmth, lymphadenopathy, lymphadenitis, leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia in patients with stabilized idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic anemia in patients who have had other hematologic disorders, paresthesia, Guillain-Barré syndrome, radiculoneuropathy, febrile convulsion, rash, erythema multiforme, urticaria, and cellulitis-like reactions.

While PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) is approved for use in children aged two and older with conditions such as chronic heart and lung disease, diabetes, cochlear implants, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, sickle cell anemia, functional or anatomic asplenia, and immunosuppression, no information on vaccine safety or effectiveness in children is available from the vaccine’s product insert.

Studies have linked PPSV23 to systemic inflammatory reactions, cellulitis and fever.

As of March 29, 2024, there have been 27,377 serious adverse events reported to the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) in connection with pneumococcal vaccinations (PCV7, PCV13, PPSV23). Over 60 percent of these reported serious pneumococcal vaccine-related adverse events occurred in children six and under. Of these pneumococcal-vaccine related adverse event reports to VAERS, 2,728 were deaths, with nearly 66 percent occurring in children under six years of age. However, the numbers of vaccine-related injuries and deaths reported to VAERS may not reflect the true number of serious health problems that occur after pneumococcal vaccination.

Even though the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 legally required pediatricians and other vaccine providers to report serious health problems following vaccination to federal health agencies (VAERS), many doctors and other medical workers giving vaccines to children and adults fail to report vaccine-related health problem to VAERS. There is evidence that only between 1 and 10 percent of serious health problems that occur after use of prescription drugs or vaccines in the U.S. are ever reported to federal health officials who are responsible for regulating the safety of drugs and vaccines and issue national vaccine policy recommendations.

As of April 1, 2024, there have been 385 claims filed in the federal Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) for injuries and deaths following vaccination with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), including 26 deaths and 359 serious injuries. Of that number, the U.S. Court of Claims administering the VICP has compensated 156 children and adults, who have filed claims for pneumococcal conjugate vaccine injury. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is not covered under the federal Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) and compensation for injuries and deaths related to vaccination with PPSV23 are pursued in civil court.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Who is at highest risk for complications from Pneumococcal vaccine?

There is a gap in medical knowledge in terms of doctors being able to predict who will have an adverse reaction to pneumococcal vaccination, and who will not.

Children receiving multiple vaccines simultaneously may be more at risk for developing complications as studies have found that children receiving the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) at the same time as the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) were nearly six-times more likely to develop febrile seizures.

Healthy adults receiving a second dose of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) within a few years of a first dose may also be at higher risk of complications as revaccination has been noted to be associated with more frequent and severe localized injection site reactions.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

Who should not get Pneumococcal vaccine?

According to the CDC, certain persons should not get PCV13 (pneumococcal conjugate vaccine), or should postpone getting it. These persons include:

- Anyone who has had a life-threatening allergic reaction to: a previous dose of PCV13; a diphtheria toxoid containing vaccine (IE DTaP vaccine); or previous dose of PCV7 vaccine, an earlier version of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, should not get PCV13.

- Anyone with a severe allergy to any ingredient found in PCV13 should not receive the vaccine. It is important to tell your doctor about any severe allergies that you or the person receiving the vaccine may have.

- If you or your child are not feeling well, a discussion with your health care provider about delaying PCV13 vaccination should be considered.

Persons who should not get PPSV23 (pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine), or should postpone getting the vaccine include:

- Anyone who has had a life-threatening allergic reaction to a previous dose of PPSV23 should not get another dose

- Anyone with a severe allergy to any ingredient found in PPSV23 should not receive the vaccine. It is important to tell your doctor about any severe allergies.

- Pregnant women should not receive this vaccine

- Children under the age of two should not receive this vaccine

- Persons who are moderately or severely ill should wait until they have recovered fully before receiving this vaccine.

Prevnar 13 (PCV13)

Contraindications to receiving the Prevnar 13 (PCV13) vaccine documented in Wyeth Pharmaceuticals product insert include persons who have experienced a severe allergic reaction or anaphylaxis to any component of Prevnar 13 (PCV13) or any vaccine containing diphtheria toxoid.

The Prevnar 13 (PCV13) package insert warns that apnea following administration with Prevnar 13 (PCV13) has occurred in infants born prematurely. The infant’s medical status as well as the possible risks and potential benefits to vaccination should be carefully evaluated prior to considering Prevnar 13 (PCV13).

Persons with altered immune systems may have a reduced response to vaccination with Prevnar 13 (PCV13). Data on the administration of Prevnar 13 (PCV13) to women who are pregnant is insufficient for Wyeth pharmaceuticals to provide any information on the risks of vaccination during pregnancy.

There is no available data on the effects of Prevnar 13 (PCV13) on the breast-fed infant and it is recommended that breastfeeding women carefully consider the possible risk of vaccination on the infant when considering this vaccine.

Prevnar 13 (PCV13) has not been studied for its potential to cause cancer, genetic mutations or male infertility. Studies on female fertility were limited to the vaccine’s effects on female rabbits.

PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23)

Contraindications to receiving the PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) vaccine documented in Merck’s product insert include persons who have experienced a severe allergic reaction or anaphylaxis to any component of PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23).

PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) should not be administered to children under the age of two and Merck warns that vaccination with PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) should be deferred in individuals who are moderately or severely ill.

Caution is advised when vaccinating any person with a severely compromised pulmonary and/or cardiovascular function where a reaction may cause a significant health risk.

PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) may not be effective for the prevention of pneumococcal meningitis persons who have cerebrospinal fluid leaks and persons with altered immune status may not respond effectively to vaccination.

PNEUMOVAX23 (PPSV23) is a Pregnancy Category C product and it is not known whether the vaccine can cause fetal harm or affect reproduction. It is also unknown whether PNEUMOVAX23 is found in human milk and as a result, Merck cautions the use of PNEUMOVAX23 in both pregnant and breastfeeding women.

NVIC Note: Some doctors only vaccinate children who are healthy and are not sick at the time of vaccination with a coinciding viral or bacterial infection. If you do not want your acutely ill child vaccinated and your doctor disagrees with you, you may want to consider consulting one or more other trusted health care professionals before vaccinating.

IMPORTANT NOTE: NVIC encourages you to become fully informed about Pneumococcal and the Pneumococcal vaccine by reading all sections in the Table of Contents , which contain many links and resources such as the manufacturer product information inserts, and to speak with one or more trusted health care professionals before making a vaccination decision for yourself or your child. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice.

What questions should I ask my doctor about the Pneumococcal vaccine?

NVIC’s If You Vaccinate, Ask 8! Webpage downloadable brochure suggests asking eight questions before you make a vaccination decision for yourself, or for your child. If you review these questions before your appointment, you will be better prepared to ask your doctor questions. Also make sure that the nurse or doctor gives you the relevant Vaccine Information Statement (VIS) for the vaccine or vaccines you are considering well ahead of time to allow you to review it before you or your child gets vaccinated. Copies of VIS for each vaccine are also available on the CDC's website and there is a link to the VIS for vaccines on NVIC's “Quick Facts” page.

It is also a good idea to read the vaccine manufacturer product insert that can be obtained from your doctor or public health clinic because federal law requires drug companies marketing vaccines to include certain kinds of vaccine benefit, risk and use information in product information inserts that may not be available in other published information. Pneumococcal vaccine package inserts are located on the Pneumococcal disease and vaccine quick facts page.

Other questions that may be useful to discuss with your doctor before getting the pneumococcal vaccine are: